On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

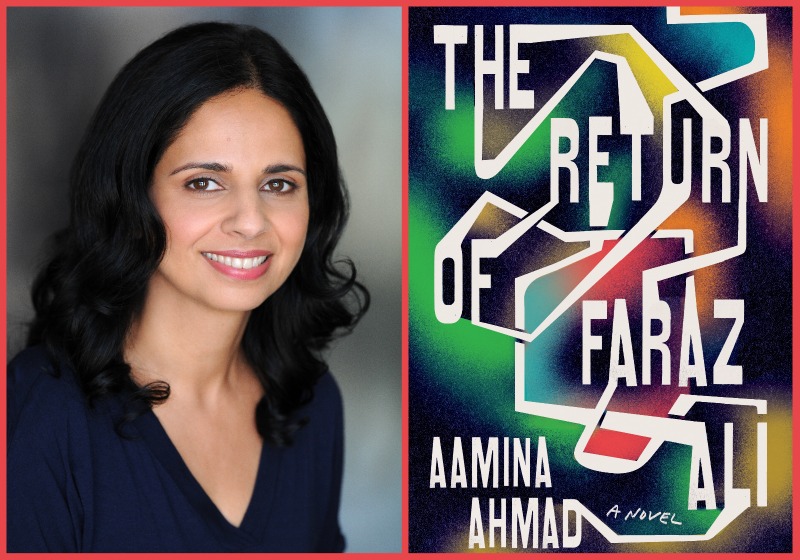

Today, we’re talking to Aamina Ahmad, author of One Story Issue #259, “The Red One Who Rocks” and the novel The Return of Faraz Ali. (Riverhead).

In late-1960s Pakistan, Faraz Ali, a young police officer, is sent to his birthplace in Lahore’s red-light district, where he was abducted as a child. His mission: to cover up the murder of a young girl. While there, he attempts to confront his past and reconnect with his mother and sister. He also starts to investigate the murder, which leads to far-reaching consequences. A gripping page-turner and murder mystery that spans from World War II to the 1971 War of Independence and traces Faraz’s family history across multiple generations, The Return of Faraz Ali explores issues of class, power, identity, and gender with depth and compassion.

—Shanzeh Khurram

Shanzeh Khurram: Where were you when you found out The Return of Faraz Ali was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Aamina Ahmad: I was at home when my agent called. It felt a little surreal! The news came just as lockdown had started in March 2020 so it was a strange time for that reason, too. We didn’t do much to celebrate but it was lovely to get to call my family and share the news; we were all locked down in various places around the world, and everyone was feeling anxious, so it felt like a bit of a silver lining, a hopeful moment, during that worrying time.

SK: Many of the events take place against a larger political and historical backdrop, from the 1968 protests against Ayub Khan’s regime to World War II and the War of Independence in Bangladesh. Along with exploring personal memories, the book also resurfaces historical moments and details that are often forgotten or erased. Can you talk about how you approached writing these personal stories alongside the historical narratives?

AA: In a way, each of the characters are very much shaped by the historical moments they find themselves in. For example, Faraz’s father, Wajid, fought for imperial Britain in World War II as a young man and grew up in an India that had been subjugated for decades. Although he might seem free, living in an independent Pakistan now, and he’s a man with a great deal of power—to me, he still seems trapped in that earlier time; his mind colonized still despite his newfound freedom.

And Faraz, who finds himself exiled and sent to what was then East Pakistan as the War of Independence begins, must, over the course of the book, confront and live with the part he plays in the atrocities that take place in Bangladesh. This is a history that many would like to erase, but one he can’t forget. So, I think throughout there is this ongoing tension in the book between the past and present, and a sense that the personal and the political are interwoven, and no one can really escape that.

SK: In your One Story interview for “The Red One Who Rocks” (Issue #259), you mention that it took you seven years to complete that short story. How long did it take you to write The Return of Faraz Ali? What was the process of writing a novel like for you?

AA: Definitely as long, if not longer! I first started thinking about writing the novel around 2012, so, it was a pretty long time between first thinking about the book and the call in 2020. In terms of the process, I loved the freedom that comes with writing a novel and the way in which a novel can accommodate so many of your interests and curiosities. As a result, when I was writing, the novel grew in ways that were unexpected and thrilling. But there were days when I felt had set myself an impossible task and wondered if I would ever finish because of the ways in which the story had evolved.

SK: Many of the women in the novel display great resilience in the face of adversity, and they do so in very different ways that at times confront the reader’s—and society’s—expectations. How did you come up with these characters?

AA: I was very conscious of the way that caste and class and gender all limit characters in the world of the story, but none more so than the women who work in the red-light district. I guessed that they lived a life that was far removed from the polite, respectable drawing rooms I was used to sitting in when I visited Pakistan, and I wondered how they managed and survived in such a socially conservative society. Because of the overlap between sex work and entertainment, acting can become a way for women who’ve worked as courtesans to ‘escape’ the neighborhood, and so a picture of a woman who has tried to forge a different path took shape and the character of Rozina emerged. Thanks to her life as a film star, Rozina does seem to access a new life for a time with the rewards that brings in terms of financial gain and recognition. However, the stigma of her history follows her around and even this new life, as an artist, proves to be a precarious one.

SK: The characters tend to be very aware of their position in society and of the extent or lack of power that they have. What’s interesting is that even characters who are in a position of authority are often constrained by something. Towards the end of the novel, Faraz’s father, Wajid, mentions to him that “sometimes a little less profile offers a man freedom.” What interested you in exploring power and freedom in this manner?

AA: I was very interested in the way institutions exert so much power over the lives of individuals, and how difficult it can be to stay true to your own values in the face of the sway they have over our lives. As you say, all the characters, even Wajid, who is a powerful bureaucrat, are very much beholden to the institutions they serve. Faraz, who is at the opposite end of the hierarchy to his father, Wajid, struggles throughout the book with this conflict. In a way, both men do find a way out, an escape of sorts, but as is the way when you take on the powers that be, whatever freedom they attain costs them in terms of position and status.

SK: What advice do you have for aspiring writers?

AA: Find community, friends, whether they’re writers or just a support system, who you can lean on when the going gets tough. It can be hard to sustain your enthusiasm, your belief in what you’re doing when you’re working on a long project mostly on your own. Fellow travelers to talk to, to complain to, and who will cheer you on (and whom you can cheer on) no matter where you are in the process can you see you over the other side. And as impossible as it sometimes seems, keep reminding yourself, you will make it over there.

Shanzeh Khurram is a writer living in the Bay Area. Her writing focuses on race, immigration, identity, and intergenerational differences. She earned an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School and is at work on her first novel.

Thoughts on “The Limits of Freedom: An Interview with Aamina Ahmad”

Comments are closed.

[…] I really struggled with the ending. Given the enormity of Humair’s mistake, it didn’t seem possible for him to reach any kind of clear resolution during the course of the story, but I still wanted it to feel as if he had traveled somewhere by the end of it. But whenever I wrote an ending, Humair seemed to drift towards it. It was when Patrick Ryan came to the story with fresh eyes and a suggestion about giving Humair more agency that I think I finally found the ending. Aamina Ahmad, author interview for One Story available online […]