On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

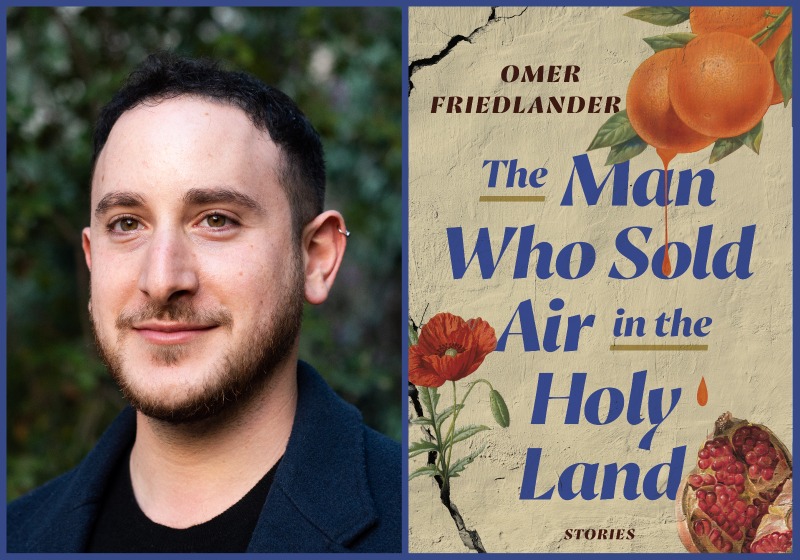

Today, we’re talking to Omer Friedlander, author of One Story Issue #287, “The Miniaturist” and the short story collection The Man Who Sold Air in the Holy Land (Random House).

In The Man Who Sold Holy Air in the Holy Land, writer Omer Friedlander captures Israel through a lens that is equally sensitive, whimsical, and critical. The eleven stories are set in both the past and present and tell the rich tales of the multifaceted people who live there. In “The Miniaturist,” which also appeared as #287 of One Story, two young girls form a rivalry when their families are forced to move to the Ma’abara immigration absorption camp soon after the State of Israel is established. In “Checkpoint,” a progressive Israeli woman volunteers at a West Bank checkpoint while mourning the death of her son, who died fighting in Gaza. In “The Sephardi Survivor,” two Sephardic brothers kidnap an old man with the intention of bringing him to Shoah Memorial Day. Through depictions of universal themes such as grief, brotherhood, and ancestral ties, Friedlander establishes himself as a writer with an innate gift for capturing the human condition.

—Mara Sandroff

Mara Sandroff: Where were you when you found out The Man Who Sold Air in the Holy Land was being published? How did you celebrate?

Omer Friedlander: Before all the celebrations, I remember feeling mostly stressed. My agent, Janet Silver, set up all these calls with potential editors about the book. I was on a trip with my family in a small village in the Galilee. My twin brother and I were celebrating our twenty-sixth birthday there. It was a small, very remote village with no phone signal, internet, or electricity. It was very beautiful—plenty of limestone and groves of olive trees—but probably the worst place to go on a week when I had to talk on the phone to several editors. My father and I frantically drove around to look for a place with reception. Finally, we found a hookah bar with WIFI. It was by a gas station off the highway, overlooking a barn. I ended up making all my calls to editors from the parking lot of the hookah bar, teenagers revving their motorcycle engines in the background. In retrospect, it’s pretty funny, but at the time…

Anyway, I did celebrate later! My future editor at Random House, Robin Desser, texted me on my birthday to say congratulations. I was out at a bar with some friends in Tel Aviv. Then the next morning, I got a call from Janet that she’d sold the book. I was still pretty hungover, but I went out to get a bottle of something bubbly.

MS: Was there a moment you realized you were working on a collection? How did that impact the trajectory of your writing?

OF: I knew early on that it was going to be a short story collection rather than a novel since it was made up of all these discrete parts, and the only unifying element was the sense of place. The stories were all set in Israel and the Middle East. I wrote them when I was living away from Israel, actually. I’d just moved to New York after a year in Boston and three years in England, and I think that distance gave me some perspective. Similarly, writing the stories in English rather than Hebrew, my mother tongue, made the familiar strange and the strange familiar.

I’m not sure whether it was a conscious decision or not, but I think it has to do with feeling like both an insider and an outsider in Israel. I was born in Jerusalem and grew up in Tel Aviv. Israel is my home, the place where the people’s way of laughing and arguing is the most familiar to me, and yet I feel like a stranger there sometimes. Writing in English gives me some distance from that home. It allows me to do more probing, to see Israel’s strange contradictions and complexities more clearly.

MS: Your stories are all set in Israel. It’s a place that many Americans first associate with the current conflict, but as your stories show, it has a multifaceted identity, and a great variety of people live there. How do you approach writing for primarily non-Israeli readers, and what do you hope they take away?

OF: Many of the stories don’t deal directly with conflict, but it is in the background. I don’t think I wrote the stories with a particular audience in mind. It’s true that the book was written in English, so perhaps it is mostly meant for English-speaking readers, but it’s also being translated into other languages—Dutch, Italian, Turkish, and I hope, one day, Hebrew.

If it is ever translated into Hebrew, I think I would work more closely with the translator. There are certain things that I contextualize for an English-speaking audience that an Israeli audience wouldn’t need. Sometimes, I use Hebrew words in the stories. Usually, I try to make it clear from the context what they mean, but it’s a delicate balance because I wanted to avoid being a kind of tour guide. I hope anyone, no matter where they’re from, is able to enjoy the stories without necessarily knowing anything about the history or politics of the place because first and foremost, it’s about people’s struggles and intimate longings and despair. That’s not unique to Israel; it’s a universal experience.

MS: Though your stories encompass different time periods, they share an interest in nostalgia and the past. This is prominent in “Alte Sachen,” which features junk collectors, and “The Miniaturist,” where the two girls are tied to their miniaturist ancestors. (“The Miniaturist” is also #287 of One Story.) Was capturing nostalgia something conscious during your writing or do you think it’s an inherent part of Israeli—and Jewish—culture?

OF: It’s very interesting that you chose the word “nostalgia” to describe some of the stories. I would actually say they are somewhat “anti-nostalgic.” I think nostalgia has a kind of haze of sentimentality to it, an idealization. With these stories, I wanted to try and see through that fog of nostalgia.

For example, in the first story of the collection, “Jaffa Oranges,” an eighty-seven-year-old Jewish-Israeli orange grower remembers an old childhood friend, a Palestinian named Khalil. They were best friends in the days of the British Mandate. In the beginning of the story, he is forced to confront the past when he meets Khalil’s granddaughter. His stories about Khalil and his memories are idealized and the way he sees the friendship is very nostalgic, but he is also avoiding the trauma and violence that ended that relationship. He’s hiding a secret, a shameful act of betrayal, and it’s only at the very end of the story that he admits it to himself. So nostalgia in this story functions as a kind of veil for the narrator, an unsuccessful attempt to forget.

Like you said, the past is very present in many of the stories, even if they are set in contemporary Israel. For example, that’s true of the title story, which follows a divorced con artist who, along with his young daughter and her one-eyed cat named Moshe Dayan, sells empty bottles of “holy” air to gullible tourists. The father takes the form of the traditional diasporic Jewish archetype of the luftmensch, the man of air, a kind of impractical person who can’t make any money, and the only way he can sustain his relationship with his daughter is through these get-rich-quick schemes and his overdeveloped imagination. The luftmensch is an archetype from the past, from the Jewish diaspora, and ironically, he’s transplanted to Israel, a place that was supposed to be the home of the “new Jew,” the antithesis of the intellectual Jew from the diaspora. So there’s a kind of clash or tension between the past and present happening.

MS: Although it’s set in the present day, that story has a distinctive fairy tale feeling, and as a Jewish reader, it felt achingly familiar. Your back cover blurb also called the stories “fairy tales turned on their heads by the stakes of real life.” How has the fairy tale form influenced you, and do you have any favorites?

OF: My interest in fairy tales and fables comes from my father, who collects old, illustrated children’s books. When I was growing up, I remember going with him to flea markets and used bookstores to scavenge for books. Some of my favorite stories growing up were fairy-tale-like. One was about a hedgehog named Shmulik, who gets strawberries stuck in his quill. Another is Room for Rent by Leah Goldberg and is about a group of animals living in a shared apartment building.

What I find exciting about fairy tales is that they offer the possibility of metamorphosis and shapeshifting and of change and transformation beyond the boundaries of what we conventionally call “real.” In the world of fairy tales, the boundaries between adulthood and childhood are blurred. Adults can become childlike in their fantasies, and children are faced with the violence and darkness of the adult world. I think keeping a connection to childhood, even as adults, is especially important for writers. My job as a writer is to daydream for a living. That’s both childish and very serious. It’s a serious form of playfulness or a playful kind of seriousness.

MS: Your upcoming work, The Glass Golem, is a novel. How has the process of writing a novel differed from writing short stories?

OF: There’s a great line by E. L. Doctorow about writing. I’m paraphrasing here, but he compares writing a novel to driving in the dark with your headlights on. You can only see a few meters ahead, and the rest is darkness. That’s definitely the way I feel with this novel, and with writing in general, for me, it’s a process of discovery. That is to say, with this novel, I’m mostly just driving around in the dark, hoping my headlights will reveal something worthwhile.

MS: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

OF: Meeting the other “debutantes.” And those paper roses, the corsages, that we get. They look very fancy. Like most Israelis, I never really wear fancy clothes. A button-up shirt is probably the fanciest I would go—maybe a jacket but never a tie. I don’t even know how to put on a tie. But I’m excited for the chance to dress up. When am I ever going to go to another ball?

Mara Sandroff writes literary criticism for Newcity Lit and will soon graduate with her MFA in fiction from New York University. She was previously an editorial intern at One Story and is an alumna of their 2019 Summer Writers Conference, as well as an alumna of Kenyon Review’s 2021 Writers Workshop. Currently, she is working on a novel that explores Jewish identity, intergenerational storytelling, and a young girl’s coming of age in a world that is (possibly) coming to an end.

Thoughts on “A Playful Kind of Seriousness: An Interview with Omer Friedlander”

Comments are closed.

[…] Friedlander also writes in English, which is a growing trend among young Israeli writers, Freedman noted. (He cited Ayelet Tsabari and Shani Boianjiu as examples.) That’s partly practical, a way of reaching a larger audience and helping control the translation process. (Books written in Hebrew are usually translated into English, and that English version is used for all further translations.) It’s also a literary device writers can use to distance themselves from the subject matter, something Friedlander references in interviews. […]