On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

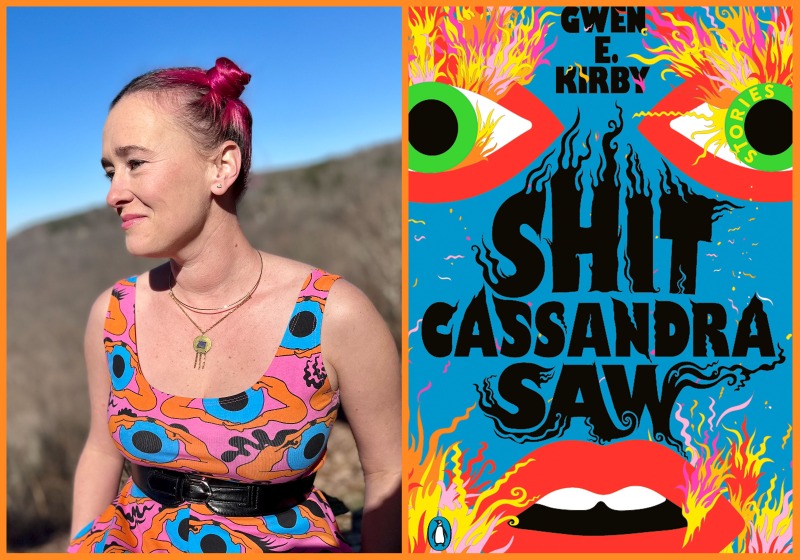

Today, we’re talking to Gwen E. Kirby, author of One Story Issue #240, “Mt. Adams at Mar Vista” and the short story collection Shit Cassandra Saw. (Penguin Books).

From the Trojan shores to the mountains of Patagonia and back, the twenty-one stories in Gwen E. Kirby’s Shit Cassandra Saw take us across time, space, and realities to present a world that is stranger, angrier, more honest, and, at times, kinder than the one we’re familiar with. Whether it’s the ladies who duel in “Scene in a Public Park at Dawn, 1892” or a fanged woman who bites a man for telling her to smile in “A Few Normal Things That Happen a Lot,” the irreverent characters we meet in this story collection challenge our expectations of women’s roles throughout history. By pushing reality to its extreme, Kirby uncovers the absurdity of our everyday lives. Shit Cassandra Saw is a heartwarming, shocking, and hilarious romp that will stay with you long after you’ve turned the last page.

—Monique Laban

Monique Laban: Where were you when you found out Shit Cassandra Saw was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Gwen E. Kirby: It was June 2020 and I was in my bedroom in my apartment. It was actually one of the few moments I wasn’t anxiously waiting for news because I was getting ready to be a host for a Zoom event for work. I had about three minutes between getting the email from my agent and starting the event and I managed to have a very efficient cry, splash my face, and decide I was going to play it cool, only to hop onto Zoom and pretty much immediately blurt out, “I sold my book!” (Playing it cool is not one of my strengths.) Because it was the pandemic, I couldn’t go anywhere to celebrate, and I was living alone, so that night I put hats on my three stuffed animals and made myself a cocktail or two and possibly had another cry. I was beside myself with happiness and with relief. I’d been working on the book for about eight years and it meant everything to me to see it through.

ML: Several of the stories in your collection have premises (and titles) that lend themselves to fun and humor, like “Boudicca, Mighty Queen of the Britains, Contact Hitter and Utility Outfielder, AD 61” and “Midwestern Girl Is Tired of Appearing in Your Short Stories.” I found myself laughing even when I felt I wasn’t supposed to, like when Megan gets so sick of men calling her and asking for Gail that she tells the next man that Gail is dead in “For a Good Time, Call,” or when Nakano Takeko dies so her sister can’t argue against her dying wish in “Nakano Takeko Is Fatally Shot, Japan, 1868.” Could you talk about the place of comedy in your stories? Do you think about landing jokes while you’re writing, or does the hilarity crop up naturally?

GEK: As is clear from the table of contents of my book, I love a long title. Not all stories need one, obviously, but often when they work for me they take on the burden of explaining the premise or form of the story so that I can dive right in to doing whatever I want, whether that is imagining Boudicca on different baseball teams or guiding Midwestern Girl through different scenes until she finds her voice. (And with historical fiction it is so convenient to stick the year in the title! Job done!) I also hope the titles help draw readers in, both to the stories and to the collection as a whole. When you look at the book’s table of contents, I think you have a pretty good idea of whether this book might interest you.

As for humor, I don’t think about landing jokes when I’m writing. If I did, I am pretty sure I would never write a funny line ever again and I am in awe of comedians who work that way. A lot of my humor comes from characters in weird situations who nevertheless act with total passion and conviction, who play it straight. The writer of the Yelp review in “Jerry’s Crab Shack” is one-hundred percent serious. He will be objective and describe the wench outfits without bias! When Megan says that Gail is dead, she’s not trying to be funny, she’s lashing out, sad to have been dumped and even more so, railing against Gail, who seems to be tormenting her from afar. The juxtaposition between their passion and pain and the targets of that passion and pain creates humor, but that’s almost a by-product of the story’s goal, which is to take its characters seriously and follow their actions to their logical (if wacky) conclusions.

ML: I loved learning about the lesser-known historical figures throughout Shit Cassandra Saw. I’ve mentioned Nakano already, but the collection also includes Gwen Ferch Ellis, Mary Read, and, while unnamed, I thought the protagonist of “The Best and Only Whore of Cwm Hyfryd, Patagonia, 1886” was very memorable. You’ve discussed your passion for history in an interview with Electric Literature—what drew you to these women specifically? What ground can you cover or space can you access by exploring the life of a historical figure that you otherwise can’t with contemporary characters? How do these women speak to our current moment or reveal something about themselves or their times that we can learn from?

GEK: I loved learning about them too! Half the reason I write historical fiction is for an excuse to do the research. I was drawn to these women for a few reasons. For Gwen Ferch Ellis and for the Welsh whore (the only character in that list who is entirely fictional), I wanted to write a bit of a corrective, a witch who doesn’t die and a whore who is unashamed. I also wanted to give voice to women whose perspectives are mostly absent from history. For characters like Nakano and Mary Read, I am fascinated by women who enter the “male” domain of war and violence and make it their own. And I really like writing about women using their bodies—to fight, to retile, to play sports, etc.—because it makes me feel more empowered in my own body.

As for what ground I can cover with historical figures, I think it is a lot easier to see the absurdity of sexism when it’s in the past. Like, obviously don’t hang that woman just because she knows how to cure a cough and you’re upset your sheep died. I hope that juxtaposing the historical pieces with the contemporary ones brings that feeling of obviously into the stories set today. Obviously don’t grope that woman. Obviously have women be protagonists in stories. The last thing I’ll say is that I love writing historical women because they make me feel part of something larger. That feeling of kinship is powerful.

ML: The historical pieces are juxtaposed against several stories that are not only set in our time but also engage with it satirically—“Marcy Breaks Up with Herself” has a reality TV show that parodies the minimalist movement and the KonMari method, and “Jerry’s Crab Shack: One Star” takes the form of a disgruntled Yelp review that turns into an inward look at a marriage. Even removed from the pop culture and digital media aspects, “Casper” feels like something of a commentary on the ridiculous amount of stuff we accumulate, with the Unclaimed Baggage Depot as a halfway point between Storage Wars and Pawn Stars. This contrast between the past and the present throughout the collection was incredibly refreshing. Could you discuss the way you approach absurdity in contemporary life as it applies to your fiction?

GEK: I think I actually started getting at this in the last question, so I’m feeling very clever! Life is absurd. And again, it’s often easy to see that in the past because we have the benefit of hindsight. But, well, you don’t need a ton of distance from the current moment to feel overwhelmed by the absurdity of it all and my challenge as a writer becomes not letting absurdity strip away meaning. “Casper” is definitely about the ridiculous amount of things we consume and throw away, but for the teenage girls who are the story’s protagonists, these objects contain meaning and even magic. Though they would like to pretend otherwise, they aren’t jaded yet, and these objects act as windows into the wider world. They are so eager for escape from their town and from adolescence that they imbue them with personal meaning, and in the case of Casper himself, a sort of personhood.

On the flip side, “Marcy” is about the fantasy that if we just got rid of everything we own, we’d be better, purified if you will, and this is as much a fantasy as the fantasy that buying one more pair of pants will finally make us happy. But while the story pokes at this absurdity, I in no way mean to poke at Marcy. This act of stripping down her life feels vital to her, a genuine effort to be, as she keeps saying, a new person. So yes, I love using pop culture and absurd forms and premises, but I have no interest in writing stories in which the characters are shamed or mocked for finding these absurdities meaningful. Past or present, we all find meaning where we can, and that can be a beautiful or at least powerful thing.

ML: In your One Story interview for “Mt. Adams at Mar Vista,” Patrick Ryan asks if you think of that story as political (and if all stories are, in fact, political), and you give a much more complex and nuanced answer than simply labeling everything as one thing or not. “Mt. Adams at Mar Vista” perhaps fits most neatly of all the stories in being read in this very charged way, but you’ve mentioned in the Electric Lit interview that “Shit Cassandra Saw” was a rageful response to the results of the 2016 election and, to NPR, that “A Few Normal Things That Happen a Lot” was inspired by the Brett Kavanaugh hearings. I would never have read either of those political moments into those stories, as they work on their own and have their own goals separate from national events. Could you talk about channeling rage and fear about current events and transforming them into catharsis and art?

GEK: I am glad that those stories don’t clearly reflect their origins, not because a writer couldn’t write an excellent direct-response story (though I don’t know if I could), but because that was very much not my goal. I think in both of those stories you can feel their origins most clearly in their openings. For “Shit Cassandra Saw That She Didn’t Tell the Trojans Because at That Point Fuck Them Anyway” the rage at the election is right there in the title, my feeling at the time that we could see directly into the future, see how fucked up everything was, and we couldn’t do a thing to stop the future coming. But the story opens in a different tone than the title, which is to say, Cassandra isn’t imagining the horrible things she’s seen, but the awesome ones. Jell-O. Claymation. For a little bit, I let myself imagine just how wild those things would seem (they still seem pretty wild) and this then leads into the sad things she sees as well, for other women, for herself. It became, for me at least, a story about resignation alongside resistance, and that was a place that I wanted to bring myself to as much as I wanted to bring my reader there.

In the opening of “A Few Normal Things That Happen a Lot,” you see that same clear link to the event that sparked it. A man is an abusive asshole but—a miracle!—he meets a woman who he cannot hurt. Then story itself becomes about complicating that narrative and asking, well, are we really not being hurt? Even if we come away from a violent encounter the victor, aren’t we still injured? Why do I even need to imagine these scenarios? To bring it back explicitly to your question, I suppose I channel my rage and fear into art that gives me comfort. I don’t think about it that way while I’m writing but I do think that was the outcome. They don’t deny the existence of what I’m afraid of but they do undermine it. They laugh at it, at least. And I like knowing that the men who inspired them would hate these stories and yet they cannot stop me from writing them or other people from reading them. That feels wonderful.

ML: What are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

GEK: I am looking forward to pretty much everything about it, from getting to go to New York to buying a fun outfit to meeting new people! But I am most excited that I get to share this experience with my mentor, Leah Stewart. Moments like this one when you get to pause and just celebrate that you made a thing, that it went into the world, that you did your best, are rare, and to have Leah with me, who helped me make that thing and rolls her eyes when I panic that I’ll never make another thing, is really special.

Monique Laban is a writer from New York. Her work has appeared in The Offing, The Florida Review, Clarkesworld, Catapult and elsewhere. She is a 2022 Hedgebrook writer in residence.