On May 16th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published or will soon publish their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

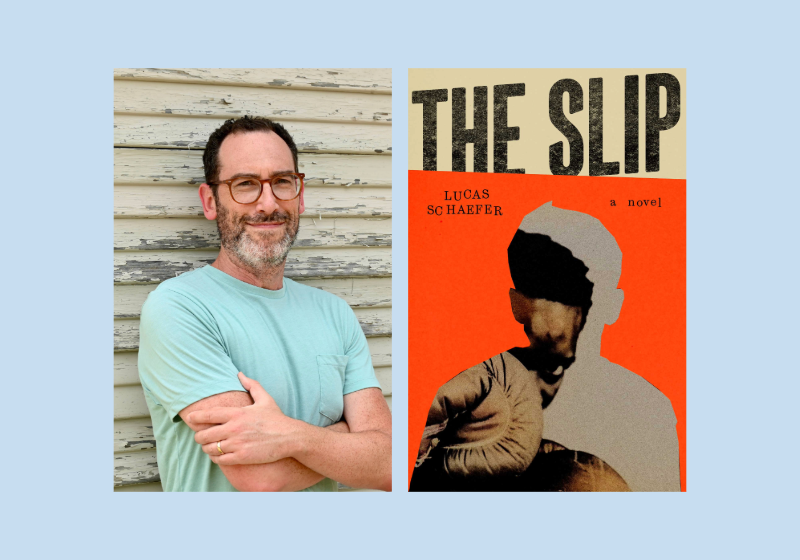

Today we’re talking to Lucas Schaefer, author of One Story Issue #225, “An Oral History of the Next Battle of the Sexes” and the novel The Slip (Simon & Schuster).

Austin, Texas, the summer of 1998. Sixteen-year-old Nathaniel Rothstein is aimless, doughy, uncomfortable in his skin, but under the wing of charming Haitian-born ex-boxer David Dalice, he’s on the cusp of uncovering another self he could be—when, suddenly, he goes missing. Ten years later, the trail of the disappeared boy resurfaces, whipping together a cast of characters ranging from a stoner professor to a migrant-smuggling clown. As this chorus of warmly and unflinchingly rendered voices drives the reader toward a revelation just shy of unbelievable, The Slip faces down the vulnerability of knowing your life might have been something greater, and the terrifying hope that maybe—just maybe—it could still be.

—J.L. Zhang

J.L. Zhang: Where were you when you found out The Slip was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Lucas Schaefer: For most of the time I was writing the book, I tutored high school and college students. To give you a sense of how long it took me to write The Slip, at a back-to-school meeting at the tutoring center where I worked, I was once gifted a watch for my service as a career tutor. It was good, consistent work, but it was many, many years of SATs and Catcher in the Rye essays. So, it felt fitting that I learned we’d sold the book as I was leaving for a tutoring session at a nearby school.

Tutoring is great because it really keeps you humble. I busted into the study room like Kramer on Seinfeld: “I just sold a novel to Simon & Schuster!” I might as well have said, “I just got back from the dentist.” The student was happy enough for me, but he had a test coming up. So, we studied for that.

JZ: In a note published a few years back alongside an excerpt from what’s now The Slip, you talk about the potential of the character to “break free of [the reader’s] gaze,” to escape the limits of even your imagination. How did your understanding of these characters evolve over the course of this project? Were there any who ran away from you, who took unexpected turns? Did you find yourself changing with them?

LS: I started this project in graduate school, when I was thirty-one. And at an early point, I came up with this character of David Dalice, who immigrated to Texas from Haiti when he was a young man. When the book opens, he’s in his late forties and long retired from a brief and unremarkable career as a professional boxer. He’s been working at an Austin nursing home for almost his entire time stateside, and he’s in a funk. David had big dreams for himself, but he hasn’t reached the levels he wanted to reach. He spends his days serving others in a way that doesn’t feel satisfying, and this leads him to make some very questionable decisions.

In those first years working on the book, I still had this big head of steam from grad school; while I understood David’s predicament on an intellectual level, his life felt pretty different from my own. But as time passed, and as I kept working on the book, and working on the book, and seeing peers succeed in publishing in ways that felt very far away for me, his situation suddenly began to feel not like an exercise for my imagination but like my situation. At thirty-one, I was so sure that even though I’d picked this tricky path, it would work out. If you work at it, it works out. But at thirty-five, at thirty-seven, at forty: reality sets in. This might not happen for you. You might, in fact, be a career tutor. Of course, the book doesn’t work if the reader doesn’t understand David or doesn’t believe he’d do the things he does. So, there’s no question that the closer I got to David’s state of mind, the better the book became. Still, it got a little hairy for a few years.

The other thing is, I’ve now known some of these characters for well over a decade. And I love them like friends. They’re real to me. And when you know characters that well, they do, as your question suggests, start to do their own thing.

I took a wonderful workshop with Alexander Chee in grad school, and he told us that the best way to ruin a story is through unmade decisions. I’ve found that be true, and am always making big, firm decisions for my characters as a result. And the way I knew I truly understood a character was when they’d start to say, “This decision you made for me? I’m not doing that. Try again.” When a character is rejecting your choices and making their own, something’s working.

JZ: Through the relationship between David and his protégé Nathaniel, the book looks at a core tension in how some of its characters conceive of Blackness: the warring, concomitant sentiments of Why would anyone want to be Black? and Of course everyone wants to be Black. In examining this tension, what guided or grounded you? How did David’s voice factor into these questions?

LS: One of the ways I stayed grounded was by allowing the characters to ground me. The book deals with these big issues—race, gender, immigration—but I knew I had to allow my characters’ individual passions and anxieties and motivations to guide me. This isn’t a story about every white kid from Newton, or every Haitian immigrant to Texas—it’s the story of these two, very particular people. That was important for me to remember when writing about these larger themes, especially race. No character is a spokesperson for their entire demographic; they’re spokespeople only for themselves.

That said, these are also characters who live in our world. Our races, our sexualities, how much money we have—all of this is integral to how each of us is perceived by others and, to varying extents, how we perceive ourselves. So, it was this combination of staying grounded in the particulars of each character, but also thinking deeply about how each character’s race or sexuality or economic status would affect how they move through the world.

I also did a lot of reading as I was thinking and writing about the racial dynamics in the book. Susan Gubar’s Racechanges was especially helpful, as was Lauren Michele Jackson’s White Negroes, about cultural appropriation, and Claudia Rankine’s Just Us. And, of course, I read John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me (1961)—a book that plays its own part in The Slip—as well as a lot of commentary on it.

As for David’s voice: for all the characters in The Slip, I figured out their “on stage” voices first, and then worked backward. So, with David, he’s got this big, garrulous personality at work, and puts on this over-the-top, dirty-talking persona when interacting with Nathaniel. That’s a voice I’d encountered in real life, and I found it easy to get down.

The tricky part was backing up and going, OK, here’s this guy who spends his days telling sex stories to his teenage underling at the nursing home where he works. How did he get to this point? And what’s he like in those quiet moments when no one is expecting him to perform?

JZ: For several characters, a transformation occurs in the ring. A more spent, resigned, mundane self is shed, and an astonishing—even dangerous—self emerges. There’s also a lot of sexual roleplay: At least three sexual relationships in the book involve some element of taking on another identity. Did these two modes of transformation emerge in parallel to each other? And how about another form of roleplay: the professional, from David’s mask at work to Miriam’s “cop face” to the Italian-nametagged staff at the Kenyan resort?

LS: I’d love to say all of this was done with intention, but I think it’s just a reflection of my own obsessions as a writer. Identity, transformation, how we’re perceived in contrast to how we perceive ourselves—that’s my wheelhouse. I do think these ideas started to build on themselves, however, so, for example, when I was struggling with figuring out the character of Gloria Abruzzi, a nursing home resident who plays a small but pivotal role in the book, it struck me that maybe exploring her Italian American identity would be a way in, since that made sense on a thematic level.

As for the sexual roleplay: I don’t want to say I’m only realizing there are three distinct instances of it right this second, as I hear your question, and yet…

But you’re right, and even if that wasn’t a conscious decision, it makes sense that in a book all about identity-shifting, so much of it takes place in the bedroom. Sex is one of the few activities in which taking on a wholly different persona from your “outside” self is not only not odd, but often welcome.

JZ: The Slip feels both like a love letter to Austin and, at times, an examination of Nathaniel’s—and your—hometown of Newton, Mass. What did you feel was important for you to transmit about these places and their people?

LS: I moved to Austin in 2006, and except for college, I’d spent my entire life in the northeast. Soon after I arrived in town, a friend who ran a nonprofit invited me to a fundraiser where the guest of honor was Bill Clinton. It was during the day and outside, but it was still a former president, so I wore a suit, which I’d hazard to guess is how most people from my part of the country would’ve played it. I arrive and I’m the only suit on offer. There are people in flip flops, in shorts. Someone asked me if I was in the Secret Service! I thought, I’m never leaving this place.

When writing about Austin, I wanted to convey that dressed-downness and juxtapose it with the more buttoned-up world that Nathaniel comes from. Here’s this pale New Englander, uncomfortable in his skin, wearing an oversized Patriots hoodie because he’s embarrassed by his weight. It felt dramatically interesting to plop a kid like that into sparsely clad Austin.

Also, there are all these tropes about who lives in Austin—whether it’s old hippies or, now, tech bros—and one of my goals was to convey the broader Austin I know. I’ve always loved writers like Zadie Smith, who use freewheeling, omniscient voices to take readers across a community. I wanted to try my hand at giving my own city that treatment.

JZ: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story Ball?

I’m looking forward to meeting the other authors and celebrating with them. Also, I’ve actually been to a debutante ball, in Louisiana in the early aughts, and for reasons too complicated to go into here, I walked away with a taxidermy bobcat that has followed me around for the last 20+ years. (She’s currently in the office closet—we have a five-month-old and Bobette has claws). So, who knows what will happen this time.

J.L. Zhang is a writer and amateur leatherworker living in Brooklyn. They’re working on a verse novel about wrestling, un-changelings, and Circle K. You can unfortunately find them on Instagram at @rrazumikhin.