On May 16th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published or will soon publish their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

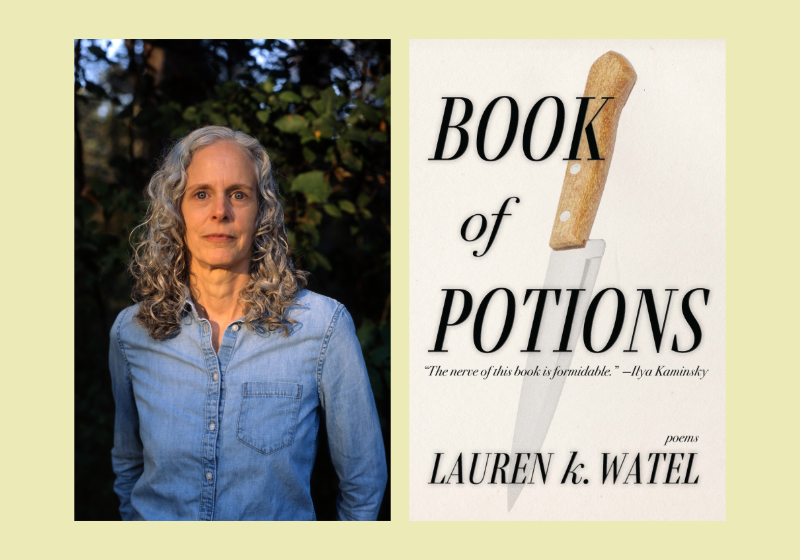

Today we’re talking to Lauren K. Watel, author of One Story Issue #321, “Trampoline” and the collection Book of Potions (Sarabande).

“Potions” is the word Lauren K. Watel uses to describe the blends of verse and story she gifts readers in this collection. The term is a portmanteau of “poetry” and “fiction” and a nod to the alchemical task of rendering the oldest of human emotions into something new. In these pieces, Watel allows love and anxiety, grief and joy to inhabit unexpected forms. She blends not only poetry and fiction, but questions, commands, and warnings; fables, dreams, and musings. Each part provides a sharp insight into the experience of living; the whole unveils its complicated beauty.

—Kimberly Huebner

Kimberly Huebner: Where were you when you found out Book of Potions was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Lauren K. Watel: I was spending time with my husband, in a rented house in the Hudson Valley that smelled like rotten eggs. As soon as I got the call from the publisher, I descended into a mire of self-doubt and a bad case of imposter syndrome. I suppose I should’ve expected it; after you spend nearly forty years trying unsuccessfully to publish a book, rejection upon rejection, roiled with feelings of frustration and envy and bitterness, plagued by the sense that you’ve been singled out for invisibility and humiliation, the entire publishing industry out to get you—all feelings, I came to see, that were untrue and unreasonable and really bonkers, but I was attached to them nonetheless—it’s somewhat complicated when you finally get the thing you’ve always wanted.

I told practically no one, not even my husband, for at least a month. Even then I was oddly un-celebratory, as if being happy about my first book would somehow curse me or cast a shadow over my greatest professional goal and accomplishment. Mostly I was relieved, and glad at a certain point that I could tell people I had a book coming out after all this time. I didn’t properly celebrate until about a year and a half after that initial phone call, at my book launch party, a raucous and joyous blowout, where I read from my book to my wonderfully supportive community, and my kid’s amazing band played, and I danced and laughed and cried.

KH: Of course, I am drawn to your use of the word “potions” in describing these pieces. What inspired you to experiment with hybrid forms? What magic can be created when we eschew the constraints of traditional genre?

LKW: Despite how it might seem, when I started writing these pieces, I wasn’t experimenting, nor was I thinking about form. During a particularly challenging, transitional time in my life, I started scribbling a page in a notebook first thing in the morning, to make myself write. I was overwhelmed by anxiety, rage, frustration, and powerlessness, and all those feelings ended up in those pages, which were never meant for public consumption. I didn’t even read them until years later. Even then I wasn’t sure what to make of this writing, as it had elements of every genre.

After I assembled a manuscript, I invented this portmanteau, “potion,” which combined poem and fiction. I thought it was clever and captured the magic that led to its creation. Which was accidental and therefore mysterious. I’d say the form ultimately created itself—out of my pressing need, my desperation to make sense of things that scared me, myself included, my impulse to unload some of that feeling onto the page. So, yes, writing out of urgency and from your darkest depths, writing to grapple with yourself and the world, writing without thoughts of genre or form, writing unselfconsciously—this can lead to all kinds of magic.

KH: As a former teacher of mine often told us, the act of reading is always a collaboration between the writer and the reader. What does a book like yours—structured in vignettes, and piecing together aspects of various forms—ask of your reader that other forms of text might not? What work do you hope your readers will put in so that they can meet you where you want them to?

LKW: Now that I finally have a book, I’m delighted that readers can encounter my writing. Whatever work they want to put in, even if none, I’m grateful they’re reading at all. In certain ways, I think the book asks less of readers than other forms of text might. The pieces are poem-like but written in prose, rather than lines, which makes them easier to digest. Also, they’re short. If you don’t like one, it’s over quickly, and you can move on. The language is mostly clear, direct, and not difficult to understand. All of which makes the work accessible. However, the potions are very intense. They are dense, like poetry, overfull of feeling and rich in metaphor. They often communicate sidewise, through imagery and fable and analogy and dialogue. Which can make them enigmatic and challenging. Each piece is a stop along a meandering dreamscape; therefore, the book demands of the reader a certain abandonment to its vision, a willingness to be swept along by the words, and the strange worlds they create.

KH: Many of these potions (the majority, by my count) include at least one question within their lines. How does the practice of questioning play into your creative process? Who is meant to consider the questions these pieces pose?

LKW: Questioning informs not only my creative process but my approach to life in general. I’m endlessly curious, and questions are my way of engaging with things I don’t understand. Even at this late date, I understand very little about the world, much less myself. I think humans are by their very nature questioning creatures, because we’re blessed, and tormented, by self-awareness. We don’t have answers to even the most basic questions: Why do we exist? Why my parents and not yours, why these places and not those, why this era and not that? What happens to us after we die? Why do we suffer? And then there are so many smaller questions, local and even trivial, that also have no answers: Why did I eat that? Why don’t I like that person? Why do I keep saying/doing the wrong thing? Why did I turn there? Why didn’t I say yes? Why didn’t I say no?

Questions are also a way for me to engage with myself, in life and in writing. I ask a question; I try to answer it. Or, I ask a question and realize I can’t answer, or shouldn’t, or won’t. To question is to engage; therefore, I believe questioning is inherently hopeful, even if the question is dire or hopeless. Because if you’re asking, you haven’t yet given up, you’re still wanting to know. Who is meant to consider these questions? Well, I am, first and foremost, because I’m the one who asked. If the reader wants to consider them as well, then great, consider away. If not, no problem, read on and don’t worry about answers.

KH: In addition to the structural fragmentation in this collection, I was interested in the references to fragmentation of the body itself. In “If Only I Could Take,” the speaker contemplates the benefits of separating head from neck; in “Nightfall,” she folds her limbs and stores them in the cupboard. How might isolating elements of the body help us to examine the self in new ways?

The fragmentation of the body you noticed in the pieces speaks to my ongoing sense of unease in my own body. As I get deeper into middle age, in a society that values a youthful appearance above all else, it’s difficult to avoid the feeling that your body’s betraying you just by enduring, every glance into the mirror a small horror. Do I always feel this way? No, but often I do, alas. Add to this the pain I’ve felt since childhood. First, my stomach. Later, neck and shoulders. Later still, back, bladder, knees, butt. For a time I had bilateral elbow pain. Which is not a thing. And yet, the pain in all these isolated body parts was very real, often debilitating, but with no mechanical cause. So my body’s been betraying me almost my entire life. Perhaps I kept fragmenting my body in the potions because a feeling of bodily integrity has eluded me. As it does many people, I assume, especially women. Pregnancy, for instance, certainly challenges notions of corporeal unity. Also, it’s possible that fragmenting and isolating body parts was an unintentional literary strategy on my part, that I was using the body to articulate the isolation and fragmentation I was feeling internally.

LKW: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

Oh, there’s so much I’m looking forward to at the ball. First of all, a ball! Thank you for giving me a chance to don a festive party frock. I just love getting dressed up and have so few occasions. Meeting the other debs will be a huge thrill. This is possibly the best part of finally having a book, getting to know other emerging writers, most of whom are considerably younger, their prodigious talent so inspiring to me. Also, having the opportunity to mingle with a dynamic literary community in Brooklyn, well, that will be ridiculously fun. I’m told the DJ is top-notch, so I’m looking forward to dancing, which I do with great enthusiasm, though perhaps not the utmost grace, according to my kid, but I’m okay with that.

Kim Huebner is a writer from Texas now living in Brooklyn. She received her MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College and teaches composition and creative writing. She also works as a bookseller and serves as a reader for One Story.