On April 27th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating nine of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

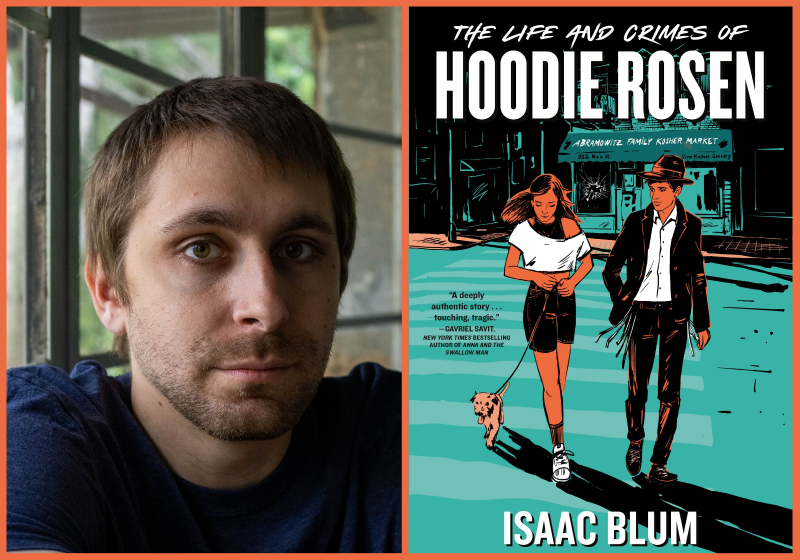

Today, we’re talking to Isaac Blum, author of One Teen Story Issue #21 “Cassie, Two Kids” and the novel The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen (Philomel).

What’s everyone so mad about? The only crime fifteen-year-old Hoodie Rosen is guilty of his growing crush on Anna-Marie. That, and maybe an overindulgence in kosher Starbursts. After relocating to the suburb of Tregaron, PA when their old town of Colwyn became too expensive, Hoodie and his family learn there’s a different price to pay in their new home. And all because Hoodie fell for a non-Jewish girl. Whether it be antisemitic slurs graffitied across Jewish headstones, or changing zoning laws to stop the construction of a new building that would mean the arrival of more Orthodox Jewish families, the residents will stop at nothing to make their hostilities known to their new neighbors. What will Hoodie do when his friendship with Anna-Marie feels so right but everyone around him is telling him it’s wrong? For the first time in his life, Hoodie is questioning everything.

The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen is a coming-of-age novel about identity, spirituality, and the power and complexities of cross-cultural relationships. Through the perspective of Yehuda “Hoodie” Rosen, Isaac Blum explores the dark side of humanity with humor, authenticity, and nuance. While Hoodie grows into the person he is meant to become, he learns an important lesson in openness and the value of staying true to himself, even while he’s still trying to figure out who that person is.

—Layhannara Tep

Layhannara Tep: Where were you when you found out The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Isaac Blum: I’m not sure exactly, because it didn’t happen in one moment. The book went to auction, so the process played out over a week or two. It was surprisingly stressful given that my wildest dreams were coming true. I don’t remember how I celebrated—good takeout, maybe?—but the best part was telling the people who’d supported me and my writing over the years.

LT: One characteristic that makes Yehuda “Hoodie” Rosen such a compelling narrator is that he always expresses his side of the story. At one point, Hoodie’s father even tells his son, “for better or for worse, it’s always clear exactly how you feel.” Hoodie’s unwillingness to suppress his truths, even when it does not cast him in the most favorable light, is a driving force in the novel. Why is this an important character trait for Hoodie to have? How does it make him the ideal narrator for the story you set out to tell?

IB: I wonder if it’s that he’s unwilling to suppress his truths, or if he’s just not mature enough to think before he speaks. Or, he might just be so naive that he can’t anticipate the consequences of his own candor. But either way, I think it works for the story in a couple of ways. At its heart, it’s a coming-of-age story, which means a lot of what’s happening is internal, in Hoodie’s own self. So it helps that he’s honest with the reader, who can clearly see his personal growth and the way he grapples with his identity. And then his candor with the people around him is what creates a lot of the story’s drama and tension. It puts him at odds with his family, his religious leaders, his community. Finally, I think it makes him a likable character, somebody the reader can root for. Because even if Hoodie doesn’t know exactly who he is yet, you know that when he does figure it out, he won’t be afraid to just be that person.

LT: I’m intrigued by the cross-cultural friendship at the center of your novel. Hoodie Rosen is new to the town of Tregaron and comes from an Orthodox Jewish background, while his love-interest Anna-Marie Diaz-O’Leary leads a secular lifestyle as someone whose family has lived for generations in the town. What role does their friendship play in the larger narrative? What lessons can we learn from their friendship?

IB: I think their friendship shows the difference between cross-cultural interaction on the macro and micro levels. The established residents of the town don’t understand the newcomers, Hoodie’s Orthodox Jewish community, and they fear them. They treat the Jewish community with a combination of implicit and explicit antisemitism. When Hoodie and Anna-Marie meet, they certainly don’t understand each other—and a lot of the plot centers around their miscommunication—but that lack of understanding turns into positive stuff: curiosity and bridge-building. Their friendship enriches both of their lives, and it shows their larger communities that there’s a path to coexistence. If there’s a lesson it’s that even one cross-cultural friendship can help to grow and heal a community, or at the very least it can serve as a model for how to build mutual understanding.

LT: Your novel addresses difficult questions about faith, cross-cultural relationships, and the ways in which hate speech can escalate into so much more. While we get an opportunity to view these topics from multiple characters throughout the book, including religious leaders, city officials, parents, the media, and even competing collective voices, it is the voice of youth that truly drives this novel. Why do you feel like it’s important to center the point of view of youth in exploring these topics?

IB: As you note, there are some difficult questions and issues in the book: faith, hate speech, antisemitic violence. I’m a fairly pessimistic person, but I wanted to write about these topics in an at least somewhat optimistic way. I find that most adults are pretty set in their biases and belief systems. But I spend a lot of time with teens, and they are amazingly open minded. They are legitimately curious about people who are different from them, who have different experiences. And they’re at an age where they know enough about the world to process this kind of stuff, but they aren’t jaded enough to lose confidence in the prospect of progress. It felt natural to center young people, because I think if you’re going to see honest curiosity and understanding, or reconciliation of opposing viewpoints, it’s going to come from youth.

LT: Hoodie and his community face hostile discrimination and antisemitism in their new town of Tregaron. At first, Hoodie does not fully understand the gravity of what is happening around him and later admits that he is surprised at how much what they are experiencing resonates with what their families in generations prior faced in the old country. Can you speak to how this reflects what is happening today? What does Hoodie’s experience teach us about what we can do to reinforce lessons of tolerance, acceptance, inclusion, and cross-community building?

IB: In the United States, more than half of all religion-based hate crimes target Jews (according to the ADL). What’s also interesting is that some of the same unfounded conspiracy theories that fuel those current crimes—Jewish control of finance, for example—fueled antisemitism hundreds of years ago. So the antisemitic tropes you see on Kanye’s Twitter predated electricity and antibiotics and indoor plumbing. It’s fascinating if you can divorce yourself from the horror of it. In the novel, the reader sees Hoodie make some of those same connections, as he realizes that he’s one link in a continuing chain of Jewish hate crime victims.

I’m not sure that Hoodie’s story can teach us how we can reinforce lessons of tolerance and cross-community building. But I think it highlights the need to reinforce those lessons. Those lessons are a constant battle, one we’ve been fighting for hundreds of years with limited success. So we have to keep working on it, and we have to start with young people (who are smarter and more mature and more empathic than we usually give them credit for).

IB: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

I’m looking forward to meeting other writers and literary-minded people. Writing is kind of a lonely gig—you do the writing part all by yourself. So I really love these rare opportunities where that experience gets to feel communal and shared.

Layhannara Tep is the daughter of Cambodian refugees and a writer of short stories. Born and raised in Long Beach, California, Layhannara is an MFA candidate in fiction at NYU. Her work can be found in Aster(ix) Journal and The Hopkins Review.