On April 27th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating nine of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

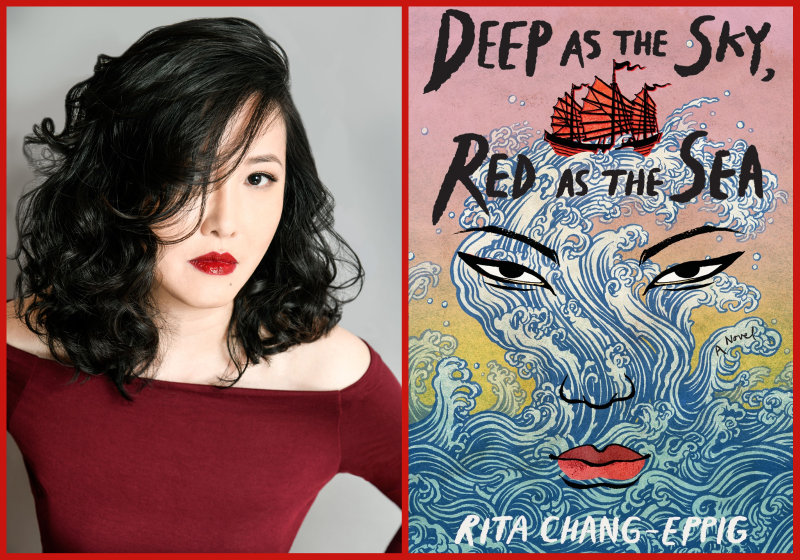

Today, we’re talking to Rita Chang-Eppig, author of OS #299, “Walking the Dead” and Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea forthcoming from Bloomsbury in May 2023.

Rita Chang-Eppig’s, Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea crosses the many borders of the South China Sea to tell an enduring story of the famed pirate queen, Shek Yeung, as she assumes leadership of a fragile alliance of pirate fleets during a time of mass poverty and social upheaval. Chang-Eppig takes a historical portrait of Shek Yeung and recasts it with contemporary urgency and humanity in this unapologetic and stunning debut.

— Emile Hu

Emile Hu: Where were you when you found out Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Rita Chang-Eppig: I was slouching around my house in a bathrobe. Glamorous, I know, but I have this bad habit in which I cannot get anything done when I am waiting for important news. So for the couple of days after I chatted with editors, I spent most of my time flopping from one soft surface onto another, cradling a jar of Nutella. After I heard, I jumped around, ate takeout from my favorite restaurant, and then immediately took a nap because I’d worked myself up too much.

EH: Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea centers on Shek Yeung’s individual story, and, in many ways, seems to be as much about the people and communities that she encounters. What was it like for you to enter into the characters’ lives and what kinds of resources, research, or people did you rely on to tell their stories?

RCE: Thank you so much for this question. This might sound obvious, but everyone exists within a social context, and my favorite stories/books are ones in which character and context play off each other. In the case of this novel, Shek Yeung’s reign is taking place during a time of mass wealth disparity and governmental abuses of power. So before I even started drafting, I read up on these social factors to help me understand what would motivate the characters. For many of them, famine (stemming from government policies) was what drove them to piracy. For others, piracy offered a way to live more authentic lives that would not have been possible on land because of sexual and religious mores at the time. I scoured dissertation archives and then also did quite a bit of experiential research in Taiwan, where both Mazuism and maritime culture are alive and well, visiting historical sites and special museum exhibits. Because you might not think a museum exhibit on Qing-dynasty kitchenware is relevant to your book, but then you start writing a cooking scene and it’s like, oh, crap. Or you’re wondering, how did people go to the bathroom on ships, and you can’t find that information in any book. Finally you learn from a random ship museum that junk ships had little ledges protruding over the water where one could, uh, pop a squat.

EH: Can you tell us a little about Shek Yeung’s relationships, the role they play for her, and one that was especially difficult, or fulfilling, for you to write?

RCE: Each of Shek Yeung’s close friends is from a different period of her life. Wo-Yuet was her protector when she was young and helpless, whereas Yan-Yan is someone she’s protecting (or thinks she’s protecting) now that she’s older and more powerful. Those relationships were fulfilling to write because I could just take a page from my own friendships: I have friends I feel a need to take care of, and I have friends who think I’m a complete idiot who needs to be taken care of. Wo-Yuet is Shek Yeung’s moral compass: she calls out Shek Yeung’s bullshit, pushes her to be a better person. Yan-Yan is more of an enabler, shall we say. For example, if you just got dumped and you’re feeling an overwhelming urge to go key your ex’s car—I’m speaking totally hypothetically here—Wo-Yuet would be the person who sits you down, offers you a cup of chamomile tea, and works through your feelings with you. Yan-Yan would immediately grab her keys and maybe also a fistful of stink bombs that she keeps in her drawer for some reason.

Shek Yeung’s relationship with Cheung Po was a little tricky for me to write. They’re both trauma survivors, and many survivors have a hard time trusting others. So you’ve got these two people, each suffering in their own way, wanting on some level to trust again but also not wanting to. Let’s just say I feel this keenly.

EH: In your One Story story, “Walking the Dead,” two young siblings follow a parade of corpse walkers in the hopes of reaching their mother and, in doing so, traverse worlds between living and dead. In contrast to Hui and Didi, Shek Yeung inhabits mythology from a vastly different position and in her own distinct way. How does your novel play with allegory, and what do you hope to bring into focus through the form?

RCE: One of the things I really wanted to explore is how we mythologize historical icons, in particular iconic women, and how we mythologize ourselves. Many people remember Shek Yeung as an irredeemable villain. Others have reframed her as a kind of feminist icon. Either way, she’s reduced to a stock figure. We also mythologize ourselves. We all tell stories about ourselves to maintain a certain self-concept, to cope with feelings of guilt, to create a sense of narrative continuity in our lives, etc. So on top of other people mythologizing her, I suspect Shek Yeung mythologized herself quite a bit to explain away her own heinous crimes.

The sea goddess Mazu (in the book, “Ma-Zou”) was part of the novel from the start because my work tends to have speculative elements. But about halfway through the second draft, I realized that Mazu was actually the perfect vehicle to explore some of these ideas. Mazu was an actual woman from Fujian, and history turned her into a literal goddess. She’s now worshipped by, I don’t know, millions of people worldwide? So I decided to have Shek Yeung’s story and Mazu’s story play off each other. How does Shek Yeung mythologize Mazu? What of herself does she see in the goddess, and what lessons does she take away from the Mazu myths? How does she use those myths to stay alive?

In contrast, Hui, the main character in “Walking the Dead,” is a child. Children generally don’t think of the world as reality vs. mythology because they inhabit a much more liminal space. For her, the walking corpses aren’t allegories or ideas—they just are.

EH: Both your novel and your story bring up questions about history and gender. One I found myself turning over is: how does gender both perform historical roles and function as a narrative structure or way of telling. For me, gender reveals and obscures Shek Yeung’s humanity and the depth of her representations. What are some of the questions you hope to ask, or came to ask, through writing your novel?

RCE: I will admit to having a lot of complicated, unresolved feelings about gender, including my own, and those feelings probably made their way into the book somehow. I’m not sure what it means to “feel like a woman,” but I sure know what it’s like to be treated like one. And gender is a key part of how many people past and present talk(ed) about Shek Yeung. The most common names people use for her, i.e., Ching Shih and Zheng Yi Sao, translate to “Zheng’s wife.” So from the jump she is reduced to a gender role. A lot of the hardships she experienced also came about as a result of her gender. So going back to myths, I wouldn’t be surprised if the historical Shek Yeung had mythologized herself as a protector of women (of sorts), given some of the policies she instituted like outlawing the rape of women captives and setting women and children free even if they couldn’t be ransomed. Unfortunately, this also meant that her victims who were not women were subject to the full extent of cruelty that pirates usually visited upon their captives.

At the same time, I do think there’s something deeply essentializing and simplistic about the way people talk about women leaders, as if they fall into a completely different category or operate completely differently from men. Nothing annoys me more than those #girlboss posts on social media, and don’t get me started on people who claim that there wouldn’t be war if all leaders were women because “women are mothers” or whatever. When the historical Shek Yeung made decisions that would affect her fleet’s survival, I don’t think she asked herself, “What would I, a woman, do?” I think she was like “What’s the best possible option here?”

I deliberately added this line at the end by the “villain,” Bai Ling, about how Shek Yeung behaved the way she did because she was a mother. Unfortunately, I think some people will take that line at face value, but it’s not intended that way. Whenever a feminized person does something, there’s a tendency for people to say, “Ah, you did that because you’re a woman/mother/whatever.” But again, I don’t think Shek Yeung made the decisions she did because of her gender. I think she made the decisions that any reasonably capable leader would.

EH: In another version of the timeline, instead of being the one who writes this novel, you are someone who comes across it and has a chance to read it for the first time. How old are you? Where are you? In this version, what does your novel give you, the reader?

RCE: I have to imagine that I would be as big a weirdo in every other timeline as I am in this one. But maybe I’m younger in some of them, in which case I hope the young mes would read this novel and take away the knowledge that they can write about whatever they want. I remember when I first started querying agents in my late 20s, I was getting feedback that essentially said, “Your prose is good, but write realist stories about poor immigrants instead of cyborgs.” Obviously there is nothing wrong with realist stories about poor immigrants, but there is something wrong with telling marginalized folks they must write about xyz. Unfortunately back then I really took that criticism to heart, and I wasted the next few years trying to write things I just wasn’t interested in. When I first met my agent in 2019, I was so scared to tell her I was working on a novel with speculative elements about pirates. But she actually seemed excited about it. And given that we were able to sell the novel, I’d like to think it worked out. So I hope young mes keep working on whatever books they’re working on, be they about cyborgs or sexy trees or murderous jellyfish.

EH: Lastly, what are you looking most forward to at the One Story ball?

RCE: I’m looking forward to everything.

Emile Hu is a trans writer from Queens, NY and currently works at New York University. They spend their time mulling over lines and trying to run in a straight-ish line with their dog.