On April 27th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating nine of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

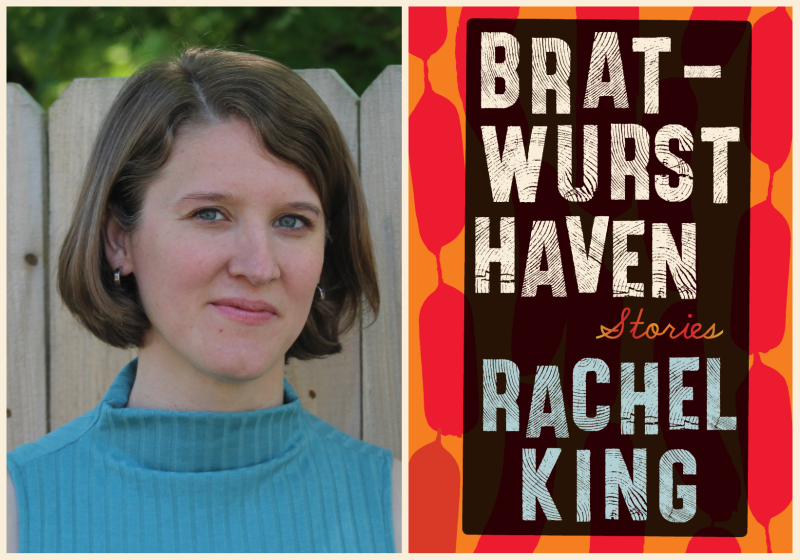

Today, we’re talking to Rachel King, author of author of OS #243, “Railing” and Bratwurst Haven (WVU Press).

Rachel King’s debut collection explores the collective and personal struggles of underpaid factory workers and their acquaintances. Set in small-town Colorado nearly a decade after the Great Recession, the twelve linked stories in Bratwurst Haven are windows into the lives of dynamic characters: a former railway engineer with a grave past, a cancer-stricken factory worker who can’t afford treatment, and a mother longing to reconnect with her infant child, among others. In honest and intimate prose, King examines how economic disparity, loss, and the search for human connection impact those working at St. Anthony’s Sausage Factory and the residents of the surrounding town.

— Zaporah Price

Zaporah Price: Where were you when you found out Bratwurst Haven was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Rachel King: I received an email that the West Virginia University Press board had approved Bratwurst Haven for publication in September 2021 while I was working from home. I’d exclusively submitted the manuscript to WVU Press a year before, and had gone through a round of revisions with both the acquisitions editor and a peer reviewer—so when it received board approval, I felt relief. Later, I celebrated by buying a bottle of Westward whiskey that I’d been eyeing at a local farmers market.

ZP: My favorite sentence from “Poker Night” is Monica’s reflection, “Time had gone slowly while she was alone.” We learn so much about these characters while they are by themselves, even if they’re amongst a sea of others, it’s their loneliness that is illuminating. Can you talk about this aloneness, and how you access that interiority of your characters as a writer?

RK: I think of interiority as a character’s soul, which Merriam Webster’s says is “the immaterial essence, animating principle, or actuating cause of an individual life.” So it’s what motivates a person, but also their essence, something deeper than motivation. I portray that by knowing as much as possible about a character: watching them, listening to them, understanding what they do and why. Allowing the outer life to continually inform the inner life and vice versa. I’ve learned that the impact of my stories often hinges on me telling the truth about my characters so I’m very careful to do that.

ZP: Some characters, like the daughter of the factory owner or the girlfriend of a factory worker, are peripheral in certain stories but protagonists in others. How did you choose what POVs to write from?

RK: I went with characters and stories that interested me. I wrote “Railing” first from the perspective of a laid-off railway engineer, then immediately wrote “A Deal” about Aaron who is also in “Railing.” Then I became interested in characters who weren’t in those stories, like Elena or Kathleen, so I wrote their stories then retroactively placed those characters into stories I’d already written. There were eleven stories in the linked collection I submitted to WVU Press, but a peer reviewer, Rajia Hassib, identified some gaps, so I removed one story, then wrote “Murals,” about the bartender, and “At the Lake,” where Elena appears again, to round out the collection. I was lucky to work with Rajia.

ZP: There are many characters in your collection who are searching for reconciliation. Whether it be with a child or with a sister, they are seeking human connection. And it’s Valerie in “Middle Age” who reflects that these connections make life worthwhile, but that “the randomness of them and loss of them” she doesn’t understand. Can you speak more to this, about these connective tissues and the loss thereof, what they mean for your characters? And more broadly, did writing this collection, writing these characters seeking reconciliation, bring you to any larger ideas on human connection and the randomness of it?

RK: The characters in Bratwurst Haven are often in transition between jobs, relationships, or apartments, and I left each story’s conclusion open-ended to reflect this reality. These characters are asking, often implicitly, Will this be a long-term situation? and knowing that it may not awakens stoicism, cynicism, anger, confusion, levity, or grief, depending on a character’s personality and situation. Regardless, most characters find comfort from human connection in the midst of their transitions, from dropping into someone else’s story or someone else dropping into theirs.

More broadly, exploring these characters’ lives has reminded me that transitory or brief relationships can be impactful, and also that some relationships can morph or return much later. For example, in “A Deal” Aaron is sure he won’t keep in contact with his coworkers, but then in “Murals” he and a former coworker get together to watch a game. Or in “Middle Age,” right after that reflection you mention, Valerie decides to reach out to an acquaintance, to try to form a friendship—so even as she mourns the very real randomness of connections in life, she also embraces the agency involved in connecting to another human being.

ZP: I found myself smiling at the fun the factory workers were having. How did you balance the economic or personal stresses many of the characters face with the joy they experience from their friendships, from their connections with one another, however fleeting?

RK: I’m so glad you found a lightness in characters’ interactions. At the factory, humor and play often begin as survival mechanisms, to distract from mind-numbing tasks, but then sometimes, when joking on the job leads to actual relationships, the characters start to share a deeper delight in one another. Often the more economic or personal issues my characters have—or maybe the more helpless they feel—the more they insist on small joys, to press back against or challenge or say fuck you to all that. It’s not going away so they might as well have fun in the middle of it.

ZP: Many of these stories have a backdrop of the recent past—Trumpism in 2016, the pandemic, the mental health crisis, lack of healthcare—just to name a few. How were you thinking about and writing through the pressing political issues that became our reality, and in many ways still is, while choosing to center your characters’ lives and bring them to the forefront?

RK: The stories probably touch on these issues because my friends or family members or myself have dealt with them—but I don’t write stories with the intent of addressing current events; a specific character in a specific situation comes to me first, then I build the story from there. As I revised these stories, I became aware that they collectively portray “moving glimpses of the many costs of underpaid labor,” as Keith M. on Powells.com notes, and I was happy that the stories subtly take that stance, but in general, I focus on character, structure, plot, pacing, and other technical aspects. An exception to that is “Pavel” which I intentionally set in the early days of the pandemic because I wanted to read a pandemic short story; at the time, in mid-2020, COVID seemed to be everywhere except in fiction.

ZP: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story Ball?

RK: Hanging out with a group of writers in NYC. I’ve been to NYC and I’ve hung out with writers, but I’ve never hung out with a group of writers in NYC. It seems like a kind of initiation.

Zaporah Price is a senior at Yale University. As an English major in the creative writing concentration, she studies postcolonial poetics and writes short stories. She is the 2022-23 apprentice at One Story.