On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

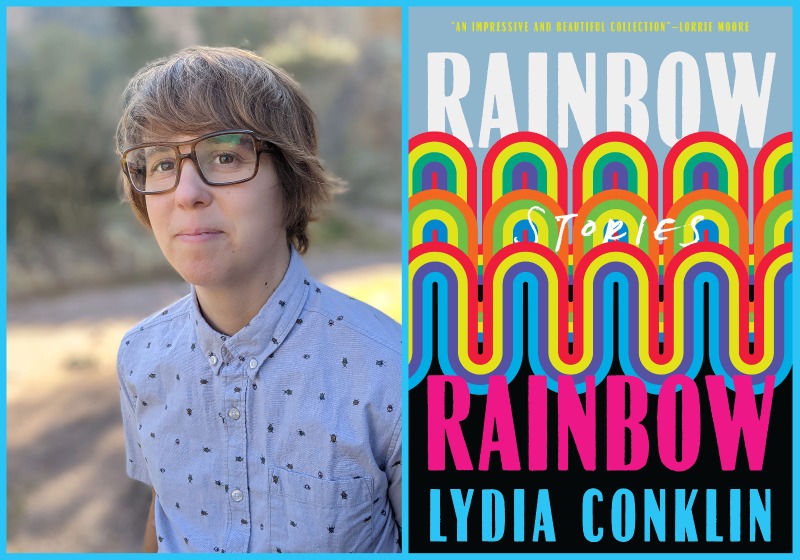

Today, we’re talking to Lydi Conklin, author of One Story Issue #285, “Sunny Talks” and the short story collection Rainbow Rainbow (Catapult).

Over the course of the ten stories of their sparkling debut collection, Rainbow Rainbow, Lydi Conklin charts the lives of a diverse, richly populated cast of characters navigating the borders and hinterlands of queer experience and identity. Conklin’s voice is startling for its emotional acuity and nimbleness, equally at home writing about formative pre-teen sexual exploration (“The Black Winter of New England”), pandemic-era intimacy (“Pink Knives”), or a lesbian couple’s fraught search for a sperm donor (“Laramie Time”). Skirting familiar tropes and worn-out narratives, Rainbow Rainbow is a refreshing and significant debut.

—Thomas Mar Wee

Thomas Mar Wee: Where were you when you found out Rainbow Rainbow was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Lydi Conklin: This is embarrassing, but I was in bed! I was in California and the auction for my book was scheduled for 9am eastern time, so I woke up and immediately checked my phone. I was so excited, it felt like a dream. Leigh Newman was such an ideal editor for me and our initial phone calls were so inspiring that I knew she would teach me so much and that we’d have an amazing time working together. I didn’t really tell anyone for a little while—this was still the darkest time of Covid and I had no one around me, so the celebration has been a bit deferred until now. But I also like to keep good news private for a while. And this was a few days before the 2020 election, so soon there were bigger things to celebrate.

TMW: There has been a lot of talk recently in the general cultural discourse about queer “representation” and especially whether or not something is good representation or bad representation for the queer community. Was representation something you thought about actively as you were writing these stories? Were there certain experiences you were determined to see represented in these stories?

LC: Yes, definitely I was thinking about representation. More in the broader concept than in the nitty gritty, but I was driven to write the book by the conviction that, while one of my favorite queer books was written by a cishet author, it’s troubling if the strongest voices in queer literature are cishet because, even if certain individual books are wonderful, disturbing trends emerge in storytelling when there aren’t queer and trans writers writing about their own experience to balance out those voices.

I also wanted to get away from certain queer storylines that have been repeated over and over—coming out stories, stories of suicide, etc. These are stories that, whether written by cishet or queer and trans authors, are stories that seem to have become what larger cishet audiences crave and expect and what Hollywood and the publishing industry feel safe and comfortable promoting, the way all non-majority identities become bound to certain stories that those with majority identities feel safe hearing over and over. Stories of coming out and suicide are hugely important in queer history, of course, but I wanted to write a book that disturbed and complicated these narratives and added nuances and distinction to the spectrum of queer experiences. I didn’t want anyone in this book to have to be a hero, for one thing, either tragic or victorious.

TMW: Related to this question, one thing I found remarkable was the sheer range of experiences represented through these characters. In these stories, we inhabit vantage points from all walks of life—an adult recovering sex addict, a middle school girl, and, in “Pioneer,” an elementary-school aged child who is experiencing what we might label as gender dysphoria. My experience reading these depictions of the internal realities of these characters is that they felt “real” or true to life. Did you encounter challenges attempting to depict such a range of experiences faithfully? And additionally, what did the “research process” for this book entail?

LC: Oh thank you so much for the nice words and close read! Yes, there definitely were challenges creating characters from all walks of life, especially those characters who behaved in ways that I would never behave. Asher in “Cheerful Until Next Time” and Lisa Parsons in “Ooh, the Suburbs” were two examples of characters that behave in dicey ways morally (to say the least) and who I had to struggle to deeply identify with. One thing that helped me through the writing process with difficult characters such as these was to embed every single character in the book with features, experiences, and personality traits of myself so I could find a way into identifying with them. Like Asher’s gender identity and presentation aligns in many ways with my own even if his actions are often alien to me. I did varying levels of research for different stories in the book. “Boy Jump” involved the most research, which I did while living in Krakow and after the fact through the help of a great friend, Adam Schorin. This involved going to sites and on tours and cross-checking histories, as well as the broader research of getting to know a place. Other stories involved sensitivity reads from trusted friends whose experience of the world aligned more closely than mine to the characters at hand.

TMW: Speaking about the collection as a whole, what unifies these ten stories for you? I assume there were other stories that you may have considered including in earlier stages of this collection. Could you speak a little about the process of selecting stories for this collection? Were certain stories written with this collection already in mind? And how did you decide which stories of yours made the final cut?

LC: So the first criteria for the collection was that all of the stories had to deal with queer or trans characters. I had some stories that I nearly included, like “Battle of the Four Seasons,” published in Tin House, or an unpublished story called “The Starlight” which deal with characters with divergent sexualities that some may consider queer but that don’t fit as plainly under the umbrella. Other stories were removed because I realized they were multiple stabs at the same material—like I had a couple other stories that covered similar ground as “The Black Winter of New England,” so for those clusters I just chose the best one.

I didn’t exactly write stories with the collection in mind but “Sunny Talks” was an example of a story that I felt was important to include in the collection as a counterpoint. Even though Sunny isn’t the point-of-view character, I wanted his experience as a youth right now to be in there to contrast against the experiences of the younger characters growing up during the nineties—what fears and struggles are the same, what’s easier now with some increased acceptance of queer culture in the media and the cishet realm, what’s harder with the Pandora’s box of YouTube and social media blasted open.

TMW: The endings of these stories were all striking to me. Each seems to end at precisely the most potent moment they possibly could. Writing good endings to stories is notoriously tricky. How do you decide when to end your stories?

LC: I struggled with the endings a lot. “Laramie Time” used to have a different, less surprising ending—the protagonist made the opposite revelation after hearing Arun’s story. Lan Samantha Chang really helped me with that story by asking the simple question: is this the most interesting decision you could make in this moment? That’s such an important question to think about while writing—how can you take the story in the most interesting direction that is possible while being faithful to who the characters are and their natural emotional responses to the situations?

Another story where the ending changed in the editing process was “Cheerful Until Next Time.” My brilliant editor Leigh Newman asked me to expand the ass-eating scene by many pages—I think at one point it was five pages long! I was a little bit baffled as to what she was getting at but then it made total sense. She wanted me to expand it so she’d have room to edit it down to its best form. That’s definitely a trick I’ll use on my own in the future.

TMW: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

LC: I’m looking forward to Leigh’s speech! And meeting many of the people I’ve worked with at Catapult in real life for the first time. I also can’t wait to be together with people in the room—such a rare treat after years of isolation.

Thomas Mar Wee is a writer, poet, and editor. Born in Evanston, IL, they currently live in Brooklyn, NY. They recently received a degree in English & Comparative Literature from Columbia University. A selection of their poetry, “Generation Loss”, was awarded a University & College Poetry Prize by the Academy of American Poets. You can find them at thomasmarwee.com and on Instagram @tmarwee.