On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

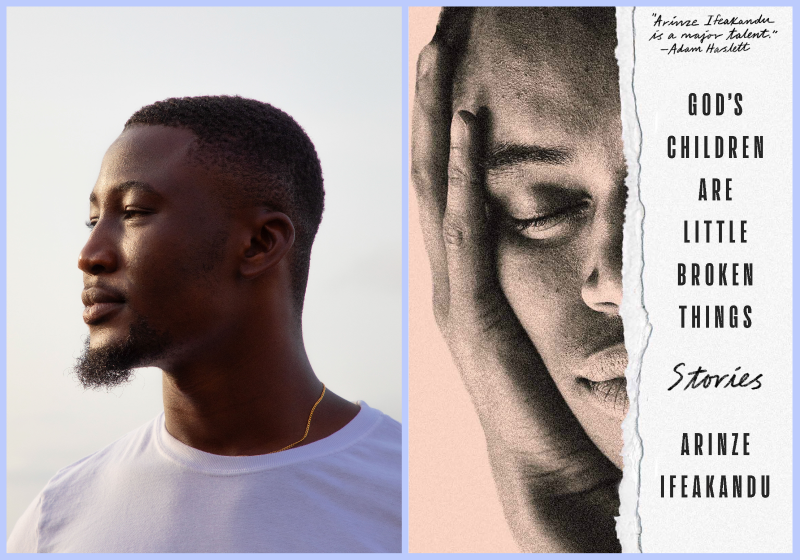

Today, we’re talking to Arinze Ifeakandu, author of One Story Issue #256, “The Dreamer’s Litany” and the short story collection God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (A Public Space Books).

God’s Children Are Little Broken Things is a collection of nine short stories set in modern-day Nigeria that explore language, queerness, and intimacy. Arinze Ifeakandu weaves an intricate tapestry of complicated lives filled with youth, love, loss, honesty, deceit, and resilience. In “The Dreamer’s Litany,” a shopkeeper struggles with his desires for an illicit lover and the reality of their divergent expectations. In “What the Singers Say About Love,” a queer relationship is tested by a singer’s newfound success. The hopes and dreams of characters are often shattered or abandoned in heartbreaking ways. In Ifeakandu’s stories we see beautifully rendered portraits, foreign and familiar, that make us laugh, cry, and better understand ourselves.

—Michaeljulius Y. Idani

Michaeljulius Y. Idani: Where were you when you found out God’s Children Are Little Broken Things was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

AI: I was in Iowa, at my second apartment on South Dodge. I don’t remember how I celebrated that very day but I recall texting and calling all my friends!

MYI: You are part of a gifted class of emerging Nigerian writers that are making an impact on the literary landscape. What do you think is distinctive about Nigerian literature and writers? What do you hope readers find unique about your voice?

AI: Thank you, Michaeljulius. Not sure I think of myself as an emerging writer in this context but to your question: every Nigerian writer I’ve read right now is doing something unique and bold, but also something for which you could find echoes in our literary history—that is immensely exciting to me. I think for me, right now, it is the diversity of our voices and styles and subject matter that does it for me.

MYI: In your One Story interview for “The Dreamer’s Litany” (Issue #256), you mentioned making changes to your story after sending it out. In that instance, the story did not yet exist in the world and was still wholly yours. Some of the stories in this collection, including the title story, which was a finalist for the AKO Caine Prize, existed in the world, and were no longer yours alone. I’m curious about how you approached revisions and changes to these stories, that also belonged to readers. Did you feel constrained or have concerns about the reactions of readers?

AI: That’s interesting—I never thought of the stories as belonging to the reader as well but that makes sense. I don’t recall having anxieties about readers’ reaction; if anything, I felt curiosity. In editing the title story, which had been published by APS, for example, I wanted to retain the syntax and mood. I had evolved as a writer and was often tempted to elongate the sentences: more commas, less periods. I had also changed as a person but I wanted readers who had fallen in love with that story over the years to recognize the hands of the wide-eyed boy who had written it. So the editorial approach was to use a light touch, like gently dusting off furniture.

MYI: Your stories illustrate the rich and complicated lives of queer Nigerian men that often disguise or hide their true selves from others, and sometimes themselves, in different ways. What were the emotional and artistic challenges you faced creating these stories? What were the joys?

AI: I’d begun the collection from a place of longing or fantasy—“here, the love I dream of”—and in those early years, the stories did not feel too emotionally challenging. In my mid-20s, and in Iowa, away from everything familiar, my gaze must have moved a little inward. Where previously I had muses, I now had thoughts to—dissect. In Nigeria, I dreamed of my future free gay life in America, my writing a ticket to that life. In America, I experienced disappointment: Even here with the law on our side, I thought, homophobia continues to keep us lonely. It was a difficult thing to come to terms to: I’d thought the great upcoming battle was about freeing ourselves from the muzzle forced on us by our fellow country people; it dawned on me, in America, that long after you’re free of the bully, you must deal with his scar, that the work had only begun. The joy was in the discovery and in the unfolding of my sentences whenever the writing was going well.

MYI: What is the one thing you would want readers to take away from reading God’s Children Are Little Broken Things?

AI: That love is real.

MYI: How did you discover One Story and what motivated you to submit your work? How does it feel to be a Debutante?

AI: Feels absolutely wonderful to be a Debutante! I’d known of One Story shortly before sending work in. It was the idea of a single story in an issue: I thought that was really cool.

MYI: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

AI: I hope to see some friendly faces!

Michaeljulius Y. Idani is an Atlanta-based writer of fictions. He is the Provost Postgraduate Visiting Writer in Fiction and a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Iowa, where he earned his MFA in Creative Writing from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.