On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

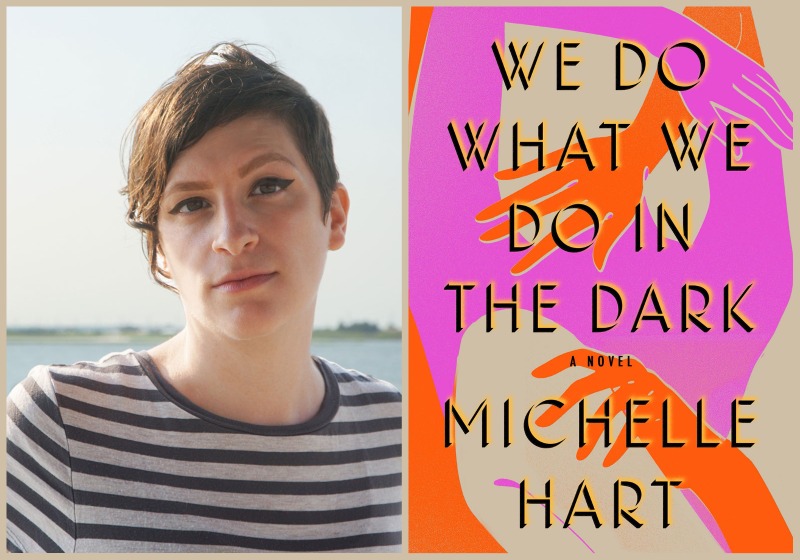

Today, we’re talking to Michelle Hart, author of One Teen Story Issue #29, “Spit” and the novel We Do What We Do in the Dark. (Riverhead).

Mallory has, or had, many women in her life. Hannah, her best friend next door when she was growing up, who kissed her, once. Her college roommate. Several girlfriends, including one with a young daughter, whose existence left Mallory speechless. Hannah’s mother. And Mallory’s own mother, who died after an illness that took up most of Mallory’s childhood. But the central woman in We Do What We Do in the Dark is introduced in the book’s first line: “When Mallory was in college, she had an affair with a woman twice her age.” It’s that relationship that will change Mallory in just about every way imaginable, helping her learn who she is, whom she loves, and why the events of her life refuse to be reduced to simple, unchanging terms.

—David Bumke

David Bumke: Where were you when you found out We Do What We Do in the Dark was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Michelle Hart: When I found out that an offer had been made to publish the book, I was toasting an everything bagel in the Hearst Tower cafeteria. I was working as a book editor at O, the Oprah Magazine, and I found out early in the morning, just as I was starting the day. After toasting the bagel, I spread some scallion cream cheese on it. It tasted great. Only after wolfing it down did I allow myself to think that my life was going to change forever.

DB: You began writing this novel before #MeToo, yet the power dynamic between your protagonist, Mallory, and the much older woman (referred to only as “the woman”) with whom Mallory begins an affair in college, raises many of the issues that have come to the fore in that movement. Did #MeToo change anything in how you wrote about your book’s central relationship?

MH: I wouldn’t say #MeToo changed how I wrote the relationship, but it did certainly clarify some of the stakes. One of the most fascinating things about #MeToo, for me, is the way it caused people—women, mostly—to recontextualize past experiences. That was always what the final part of the book was about: how would this relationship look in another light? The affair is a secret for so long, a story only Mallory knows, so how would she recount that story to someone else, how would another person receive it? Would Mallory feel protective of the relationship and resist defining it through external context? As you alluded to, I think the novel participates in other elements of the #MeToo conversation: the role of influence in intimate relationships, questions of autonomy in relationships between two people who are different in age and station. But what was exciting to me, and this was augmented by the larger cultural movement, was how our perceptions of formative relationships can shift over time—for better or worse.

DB: Mallory has recently lost her mother. Of all of the important women in the book, she may be seen the least—and yet her absence affects Mallory constantly and profoundly. Was it a conscious choice to keep the mother largely offstage?

MH: You know, until you asked that question, I’m not sure I ever considered the mother as existing “largely offstage,” but I suppose you’re right! In a way, Mallory is defined by that absence; a mother-sized hole exists in the narrative of her life, and the narrative of the novel reflects that. Mallory’s mother had been sick for a lot of Mallory’s life—age ten to eighteen. I don’t think Mallory ever truly knew her mother. Or at least, she doesn’t feel like she did. There’s a scene in which Mallory asks the woman what the latter’s mother is like and the woman lists these idiosyncratic specifics, which leaves Mallory a little dumbfounded; she wants to, but can’t, list her own mother’s idiosyncrasies. It’s kind of heartbreaking.

DB: Before she meets the woman in college, Mallory has another relationship with an older woman, Mrs. Allard—the mother of Hannah, her once-close friend and next-door neighbor. It’s not overtly sexual, and in some ways, Mrs. Allard serves as a stand-in for Mallory’s mother, who at the time is in the hospital and not doing well. Chronologically this brief but intense connection with Mrs. Allard happens before Mallory meets the woman, but it doesn’t appear until well into the second half of the book. Can you talk about this structure and your decision to include that relationship at this juncture in your novel?

MH: First, thank you for this question! Writers spend a lot of time thinking through the craft elements of their work and are so rarely asked about them! It may or may not surprise you to know that there were versions of this novel that began with Mallory’s childhood and then followed her to college, where she meets the woman, and then jumped ahead. The shortcomings of that original structure were such that the affair was a thing that happened and not the thing. By beginning with it, it becomes the narrative’s center of gravity. And to go back to that idea of recontextualizing the past: rewinding from the affair to her childhood gives the latter a greater charge. It makes her somewhat mundane childhood more interesting. Knowing what will happen, the story becomes reoriented towards asking, How did she end up there? What made her who she is? I think this is how a lot of queer people experience time: we’re constantly looking back to find evidence of our current selves. So, I guess you could say that the novel itself has a queer structure.

DB: You write about Mallory in the third person, and there are times when the narration feels almost intentionally distant from the character, even when it is relating Mallory’s thoughts. Yet the sum effect is intensely personal. What can you tell us about your approach to point of view in this novel?

MH: I wrote drafts of this book in first person, and they were probably fine, but third person offers both more possibilities and restricts certain bad impulses. My mentor, the very brilliant Akhil Sharma, has this thing about first versus third that really helped me; first person generates higher stakes, since what is occurring and what is being observed is tied directly to the narrative’s consciousness (the “I”), while third person burns plot at a more rapid rate since the “I” is removed. So, in first person, you could have more interiority and less plot, because something is always “happening,” but in third person you have to sort of get on with things. As such, changing the book to third person sped it up.

DB: “Spit,” your story in One Teen Story, also involved a character named Mallory, who was dealing with feelings she had for her best friend, who was about to leave for college. What made you decide to continue writing about Mallory? And is this the last we’ll see of her?

MH: After I wrote that story, I wrote another about a student who has an affair with a teacher. I looked at the stories side by side and thought, The protagonist of these could be the same. They were dealing with similar things; they were both girls learning how to be women. So then, really, it became about filling in the narrative gaps. Right now, I’m working on a novel that is quite different—though I suppose similar in some regards—but I have been tempted to revisit Mallory. The last chapter of the book, the epilogue, in which Mallory is dating a woman her own age, was initially much longer, spanned a much greater length of time. Ultimately, I shortened it, since the story stopped being about the initial affair. But I’m very interested in how Mallory goes on now. Will she see the woman again? What would the circumstances need to be in order for that to happen? Part of me can envision a sequel à la Before Sunset/Before Midnight, the two characters meeting a decade later. That could be interesting!

DB: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

MH: Celebrating (in person!) with Patrick Ryan, who was the very first person to edit my fiction. His early encouragement gave me the confidence to pursue writing fiction as a career, and I think it’s fair to say that this book might not exist without him. I’m very grateful!

David Bumke is a writer and editor and cofounder of the Tri-State Tough writers’ group. He is working on a novel about an estranged couple whose college-age daughter disappears.