On June 3rd at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating seven of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

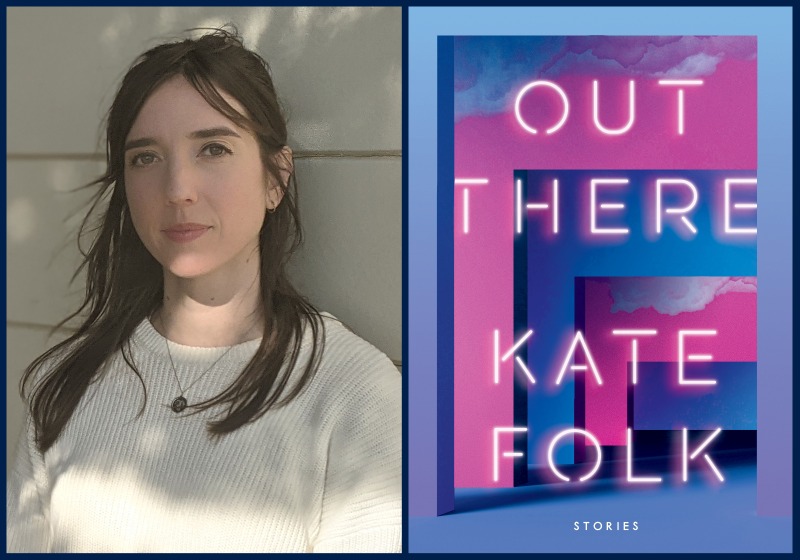

Today, we’re talking to Kate Folk, author of One Story Issue #235, “Pups” and the short story collection Out There. (Random House).

Provocative, prescient, and wonderfully weird, Kate Folk’s debut collection Out There dazzles as Folk deftly fuses elements of science fiction and gothic horror with quotidian realism to explore what it means to live in these strange times. With an absurdist’s eye for human foible and flaw, Folk drops world-weary Alices into uncanny valleys populated by organ fetishists, biomorphic humanoids, and sentient houses. The coyotes are at the door as the void closes in, and yet, however bleak it seems out there, in Kate Folk’s world, humor and humanity abound.

—Julie Innis

Julie Innis: Where were you when you found out that Out There was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

Kate Folk: The day I got the deal was the same day my New Yorker story was published online, and the day the mayor of San Francisco announced a shelter-in-place order to begin two days later. It was Monday, March 14, 2020. It was a strange, surreal day. My professional dreams were coming true, but it all seemed trivial compared to what was happening in the world. It felt kind of grotesque. Although of course I was also thrilled. Very confusing. I’m not sure what I did to celebrate on the actual day. I think I ate jarred fruit cocktail and Eggo waffles and watched Love is Blind.

JI: Maybe it’s the nihilist in me, but I love how your stories tease out the dark humor present in the bleakest of situations and I was surprised to learn you’d actually finished this collection pre-pandemic, given its overall pandemic lockdown / End Times vibe. Does your creative process require a certain daily dose of apocalyptic dread? How do you manage to keep your writing hilariously mordant in the midst of <gestures wildly> all this?

KF: I’ve always been fascinated by creepy and disturbing subjects. I’ve spent many nights right before bed plunging down an internet rabbit hole about some topic. Reality is disturbing, and I have the notion that it’s better to just confront it rather than letting my imagination fill in the blanks. I’m talking about stuff like the oceans and outer space. Terrifying to read about. I think for me it all comes back to climate change, which I’ve known about in some way since our first-grade teacher showed us a video about how the earth was in trouble, circa 1991 (I think back then the focus was mostly on the hole in the ozone layer and deforestation, but the projections were still very bleak). I never shook the sense of dread I felt that day, and it seemed like nothing I did really mattered in light of it. I think the climate crisis informs everything we write, even if we aren’t writing about it explicitly. It’s like we’re trapped in a slow-moving horror/apocalypse movie, and it feels like there isn’t much we can do about it as individuals, so we just kind of go about our lives as usual while the world falls apart around us at an accelerating rate. Not to be a downer, haha.

JI: Your One Story, “Pups” (Issue #235), while in many ways similar in tone to the stories assembled in Out There, falls more solidly in the vein of realistic literary fiction than much of your work does now. In your interview with us at the time, you spoke about how your writing was becoming “progressively weirder.” How did this progression toward the weird begin? Did you make a conscious decision to move in this direction or did it happen more organically? What has this move opened up for you and your work?

KF: It happened organically. I was drawn to weirdness in fiction I read, movies and shows I watched, and my mind started kicking up increasingly absurd concepts. Partly it’s realizing that everything has already been done in fiction, many times over, so I’m trying to find a fresh angle to get at the essential weirdness and absurdity of the human experience. I also write largely to entertain myself. The novel I’m writing now actually isn’t speculative. The narrator and her particular obsession are unusual, but the elements of her world are realistic, so it’s more of a character study. Another step in my evolution, I suppose.

JI: Speaking of evolution, where did this collection start for you and what guided your selection process?

KF: I’ve been putting together different versions of collections for years, as I’ve continued writing short stories. Out There came together with the two blot stories, which, along with “Moist House,” are the most recently written pieces. Past collections I’d put together didn’t feel thematically cohesive enough, and the blots really tied things together, I felt. I tried to curate the stories in this collection to reflect similar themes and create a unified vibe. I liked the idea of stories mirroring each other, and also for the first half of the book to be more harrowing, and the second half more hopeful—hopeful in a skewed way that suits the book, of course.

JI: Both “Out There” and “Big Sur” feature your fantastic creation, the “blots,” AI lotharios designed to seduce women in order to steal their personal data. Can you talk about the impulse to book-end your collection with these two stories?

KF: Once I’d written both stories, it seemed obvious to me that the book should start with “Out There” and end with “Big Sur.” I workshopped “Out There” in the Stegner program and was encouraged by the feedback to continue exploring the world of the blots. In “Out There,” we don’t meet a blot in the present scene—we only see one filtered through the narrator’s memory. So I wanted to write a story in which the blots were present, and with a blot POV character, because I was fascinated by the way they would think. I didn’t want the blots to be villains. In many ways I find them more endearing than the human characters in the story. They can’t help the way they were programmed, which might be the most human thing about them.

JI: Many of the stories in Out There explore the ways in which our most primitive drives keep surfacing regardless of how technologically advanced we become. What draws you to this theme?

KF: Technology is created by humans, and as such it reflects us, or who we think we are, our values and desires. It can heighten and distort drives that are already in us, but I don’t think it creates anything completely new in terms of our interactions and feelings. Though of course, society and daily life is completely transformed from what it was even fifty years ago, and it’s kind of scary because we haven’t had time to evolve and develop the necessary wisdom to wield technology responsibly. It’s terrifying to think about the effect the internet must be having on our brains.

JI: In “A Scale Model of Gull Point,” the protagonist chooses to create art in the face of destruction. What do you see as the role of art in our time? What has the act of writing these stories clarified for you about the connection between art and life? Do you write to make sense of the world around you or to create worlds that make sense?

KF: I see that story as having several possible readings. It’s beautiful, in a way, that the narrator prioritizes art as things are crumbling beneath her, but it could also be seen as solipsistic, missing the big picture because she’s so focused on her internal world and self-conception as an artist, so that rather than saving herself (or helping anyone else), she remains fixated on crafting these objects out of foil until it’s too late. I do wonder sometimes whether writing is the most useful way to spend my life, from a moral standpoint. But, I try not to worry about that too much, because I know I’m going to keep writing.

JI: How has living in San Francisco informed your writing? Would you be writing different stories had you stayed in Iowa?

KF: I’d definitely be writing different stories if I stayed in Iowa. I wonder what they would be like. I went to college in New York, and the early stories I wrote there were set in Iowa; I think I needed a little distance from where I grew up before I could write about it. But now that I’ve lived elsewhere for almost 20 years, I’m too distant to write convincingly about Iowa, except through the lens of nostalgia. I think San Francisco has seeped into my writing in so many ways. The tech culture, the dystopian inequality, the absurdity that goes along with so much money concentrated in one place. And there’s also the gorgeous landscapes, the fog, the year-round chill, and vestiges of a wilder past San Francisco that persist. I do love it here, though I’ve never considered the city a long-term commitment, which might be part of its appeal.

JI: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

I’ve heard it’s the literary event of the year, so I’m very excited to attend! I’m looking forward to seeing old friends and meeting new ones. I need to get a dress, I suppose.

Julie Innis is the author of the short story collection Three Squares a Day with Occasional Torture. Her work has appeared in The Greensboro Review, Gargoyle, and Post Road, among others.