On April 27th at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating nine of our authors who have recently published their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

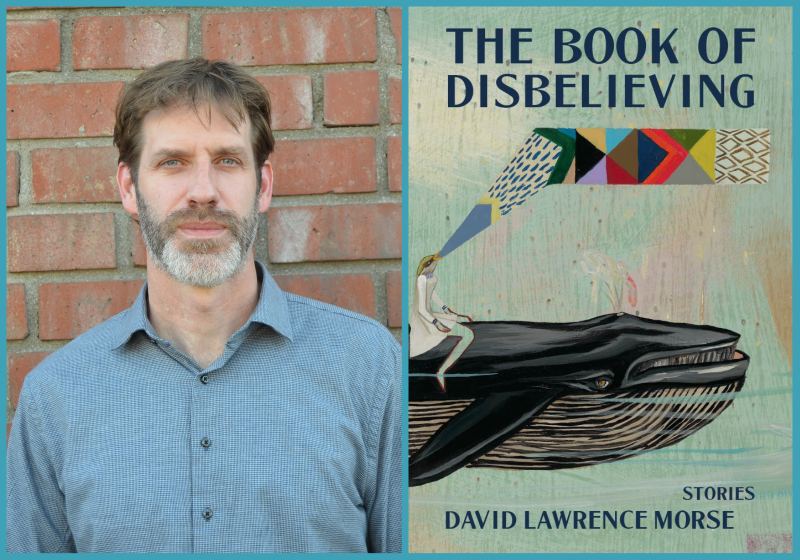

Today, we’re talking to David Lawrence Morse, author of author of OS #43, “Conceived” and The Book of Disbelieving (Sarabande).

David Lawrence Morse’s debut collection of stories, The Book of Disbelieving, won the 2022 Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction and is forthcoming from Sarabande Books in July 2023. Exploring different aspects of reality and fantasy, as well as the relationship between them, the stories in the collection present a cast of characters confronted with their belief: in God, in nature, in memory, and self. Drawing inspiration from folklore, mythology, literature, and history, Morse’s collection challenges perceptions of truth and fiction. In this interview, Morse shares thoughts on writing, reading, and disbelieving.—Michaeljulius Y. Idani

Michaeljulius Y. Idani: Where were you when you found out The Book of Disbelieving was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

David Lawrence Morse: I was in the dining room—this was when my family and I lived in Detroit. Outside the dining room window, there was this incredibly lush weeping silver birch and I remember the sunlight radiant in the leaves. The email came in, and at first I just casually glanced at it thinking it was either junk mail or another form letter rejection from a literary magazine or press. It took a while to realize that this particular message was different. I think when the reality dawned on me, I said something prosaic and understated like, “Wait—hold on.” A few minutes later, I was on the phone with Kristen Renee Miller—the editor at Sarabande. I don’t recall much in the way of actual celebration—besides the obligatory round (or more than one round) of alcoholic beverages. The celebration for me was more internalized—just felt an immense gratitude and relief.

MYI: I love the title of your collection! How do the stories challenge our perception of reality and invite us to question our own beliefs and assumptions?

DLM: Thank you, that’s an excellent question.

Ultimately the goal with many of the conceits in the collection is to hold a funhouse mirror to reality—to exaggerate or distort a particular custom or belief and so to invite the reader to examine that custom or belief in a new light. The way that our culture conceptualizes death, for example, is radicalized in a couple of stories. Another story exaggerates the literalness with which a certain type of believer tends to think about the afterlife.

Many of these stories also try to situate the characters’ beliefs within the larger society in which they live. When readers encounter various apparently bizarre collective beliefs in these stories—for example, the custom that the best way to reach heaven is to leap off the roof of your home, or the belief that to die on land rather than water constitutes an affront to God—I hope that they’ll pause to think about which of their own customs or beliefs might derive from their own community or cultural traditions, and how these beliefs might seem strange or even outlandish to an outsider.

I also try to show how some individuals will invariably resist collective customs and beliefs—for various reasons. Some, like Osa in “The Great Fish,” have radical imaginations—they have their own visions that contradict the beliefs of the group. While I intend these stories to celebrate such visionaries—their heroic and fanatical independence—I also want to explore how the boldness required to break with prevailing opinion can itself be dangerous and lead to risky choices inspired by visions with a possibly dubious relation to the truth.

Others are compelled to resist the beliefs of the group by circumstances—like Ameline in “The Market” or Daniel in “The Serial Endpointing of Daniel Wheal”—where the group’s belief system threatens or harms them in various ways and they become pariahs, either by choice, like Ameline, or against their will, like Daniel. Being cast out of your community is destabilizing. You don’t know where you’re at—who or what to believe. I hope readers will see how contingent the security of their own beliefs is on circumstance—and how it doesn’t take much in the way of accident or malevolence to call that belief system into doubt.

MYI: In your One Story Interview for “Conceived” (Issue #43), you discussed the challenges you face creating “the right combination of setting, voice, point of view, characters, and conflict, that will propel the story forward.” What were the challenges and process for choosing the right combination of stories that could propel the collection forward?

DLM: I’ve written quite a few stories that didn’t make it into the collection—some because they lacked any immediately recognizable element of the fantastical, or because the element of the fantastical seemed too arbitrary to me and I could never make sense of it, or because, no matter how many times I revised them, in the end they still kind of sucked (maybe I’ll figure out how to fix them someday). Each of the stories in the collection—unlike the rejects—hits a sweet spot for me personally, where the fantastical elements are both easily comprehensible on a certain superficial level but also at the same time deeply resonant, that is, capable of suggesting interpretations that might not have occurred to me but might occur to others.

The next step was determining the order. There was some logic to it. “The Great Fish” needed to come first because it’s perhaps the boldest conceit and announces to the reader that in these stories anything is possible. Then it was my editor Kristen Miller’s idea to put “The Book of Disbelieving” next in order to demonstrate the two poles within which these stories would operate—extreme speculative fantasy on the one hand, subtle manipulation of a more domesticated reality on the other. After that, there was a certain amount of intuition involved, but I did want the collection as a whole to transition toward stories in which the main characters are wrestling with a recognizable postmodern nihilist sense of despair. You could say that the stories grow up or mature as the collection progresses—imaginative exuberance gives way to age and anxiety.

MYI: What would be the one thing you hope readers take away from the collection?

I’ve talked already about the major themes that are important to me—so maybe here I’ll just say that the one thing that I hope readers take away from the collection is the belief that’s contained in its very publication. Yes, the characters in the collection struggle with their own doubts about their beliefs. But writing these stories required an inordinate amount of belief. They were written over the span of almost twenty years. Some of them have been rejected by dozens of literary magazines. Two were originally written as complete novels that themselves took years to write and were rejected by dozens of publishers. It wasn’t always easy to keep writing stories in the face of so much apparent indifference and rejection. It required equal amounts of caffeine and self-discipline and what felt like self-delusion to keep going. So you’re probably wondering: belief in what? I don’t know exactly. Belief in the value of hard work and perseverance. Belief in the virtue of daily creative engagement with the universe. Belief in the necessity of asking questions while never committing to a supposedly coherent set of answers.

MYI: I’m sure you are often asked about writing advice, but I’m curious to know what advice you have to offer about reading?

DLM: To be honest with you, as I’ve gotten older—and as I’ve written more and read more from the perspective of a writer—my relationship to reading and to books has changed. I’m nostalgic for the halcyon days in my early twenties when I’d learned enough about literature to appreciate its subtleties but hadn’t read enough yet to grow accustomed to what you might call the tricks of the trade. I was a voracious reader then—capable of being inspired into something like euphoria by all manner of conceits and devices and styles. I’ve grown more world-weary as I’ve gotten older. So one tactic that’s helped me to retain the sense of urgency that I read with in my youth is to read with a purpose. Either for a new course that I want to design and teach, or a writing project that I hope to tackle, I’ll choose a topic that I know little about, then attack that topic by reading as widely and as deeply as I can across genres—literature, politics, history, philosophy—whatever is relevant. It’s great. I start from a place of ignorance, and I don’t like being ignorant, so I’m inspired to read with gusto, acquiring new knowledge and discovering new aesthetic horizons along the way.

MYI: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story Ball?

DLM: One Story is such an extraordinary publication—I’m looking forward to meeting so many other authors published in its pages—and the magazine’s other supporters as well.

Michaeljulius Y. Idani is an Atlanta-based writer of fictions. He is the Provost Postgraduate Visiting Writer in Fiction and a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Iowa, where he earned his MFA in Creative Writing from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.