On May 1st at our Literary Debutante Ball, One Story will be celebrating four of our authors who have recently published or will soon publish their debut books. In the weeks leading up to the Ball, we’ll be introducing our Debs through a series of interviews.

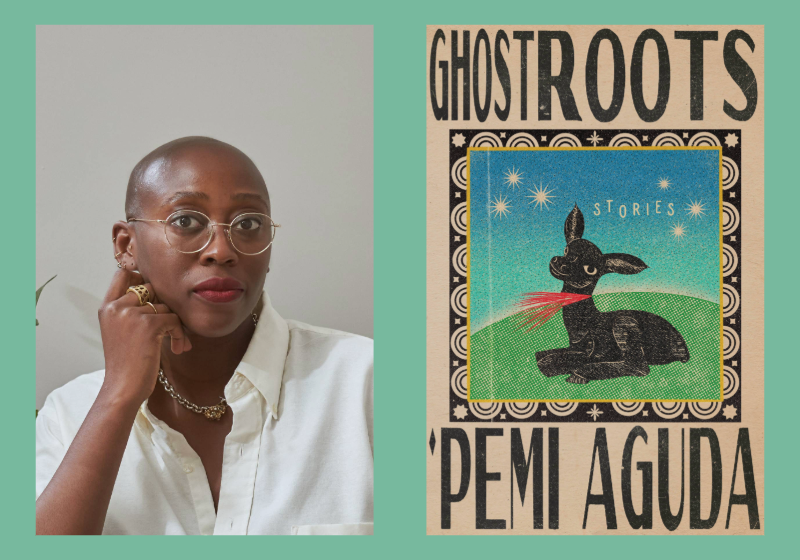

Today, we’re talking to ’Pemi Aguda, author of One Story Issue #277, “Breastmilk” and the short story collection Ghostroots (W.W. Norton).

In Ghostroots’ twelve stories, ’Pemi Aguda plants us among the vanishing markets and shape-shifting houses of a richly imagined Lagos, Nigeria. There, past and present bleed together, and the living embody the dead. Its inhabitants grapple with ancestral ties that often feel too tight or too loose and weigh invitations to believe in miracles or magic. While the ground may shift beneath these stories, the roots within their narratives reach to profound depth.

—Kimberly Huebner

KH: Where were you when you found out Ghostroots was going to be published? How did you celebrate?

PA: I was crossing a Philadelphia street. I didn’t live here then, was just visiting to see if I could. Renée (my agent) called, asked, “Are you sitting down?” To celebrate, I ordered Senegalese food and feasted alone in my Airbnb.

KH: An overarching theme of this collection involves the through lines of generations and how those lines may be extended, woven, or severed. What drew you to this theme? What about it did you find most interesting to play with?

PA: Are we only defined through the context of family/genetic history? And who could we be, free of that framing? Depending on the day, one or the other question feels unfair, even sacrilegious. My fixations only reveal themselves after the story is done, and the oldest of these stories is almost a decade old. I started to truly ask these questions of myself in that mid-twenties era of young adulthood.

KH: There’s a line in the story “Breastmilk” that asks, “But what would the scar say if it could speak? If the body could tell what it doesn’t forget, doesn’t process?” In several of these stories, the body seems to manifest spiritual states or changes. Can you speak to how you use the body as a vessel for drawing out story and character?

PA: I am fascinated by psychosomatic responses. The belly ache after a bad interaction. The rash on the neck after a missed phone call. The twitching of an eye when you suspect a lie. I used to think of my body as just a shell for my mind: something to be fed and exercised and covered in clothes. How foolish. While a body is a body—as in, a container, a body is its own system of intelligence, separate and complex. If what I’m saying is pretty obvious, it wasn’t always to me. In fiction, I enjoy when the body seems more intuitive than the logical mind’s consciousness. The character in Han Kang’s “The Fruit of my Woman” slowly morphing into a plant. How Arit keeps scratching her wrist in “The Hollow.” These characters might not yet have acknowledged a reality or idea, but their bodies are miles ahead, and the catching up can be fun to write through.

KH: In many of these stories, characters are trapped or confined. In some cases, this is by a physical container (a body, a house); in others, by a more abstract one (a past, a cycle, a societal debt or expectation). What can confinement elicit from a character? What can we learn from characters who are challenged with freeing themselves, or with deciding whether it is worth it to try?

PA: None of us are free, but I hope the lesson is that it’s always worth it to try. Even if freedom doesn’t taste like you expected. In fiction, trapping a character pushes the repressed to the surface, forces them to look—at the world, at themselves. I used this analogy in a recent Tin House craft intensive on crucibles in fiction: A woman wears a mask. If you put her in a “sauna,” then the heat, the steam, might force her to take it off, even for a moment. In that class, we discussed “Skinned” by Lesley Nneka Arimah—the main character is trapped by that society’s customs around marriage, but after she ventures outside of this constraint, she sees that her new “freedom” is in itself a privilege. None of us are free until we are all, but she might not have reckoned with that until she stepped out of her own confines.

KH: Speaking of containers, the short story form feels like a kind of container itself. Why did you choose that container to tell these stories? What about the short story form appeals to you as a writer?

PA: Joy Williams said, “The significant story possesses more awareness than the writer writing it. The significant story is always greater than the writer writing it.” I feel the mysticism of writing more with short stories than longer pieces. That magic-guided unknowing. Not knowing where I’m going until after I have arrived. On the other hand, my experience of writing a novel, so far, has been that I need more awareness, more planning. When an idea comes, I don’t make deliberate choices between a story or something else. They arrive as stories and I don’t poke at the mystery.

KH: Lastly, what are you most looking forward to at the One Story ball?

PA: The outfits: Uche’s, Puloma’s, Shannon’s. And, dancing! If photos of the previous balls are to be believed, then I’m ready to move.

Kim Huebner is a writer from Texas now living in Brooklyn. She received her MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College, where she teaches composition and creative writing. She also works as a bookseller and serves as a reader for One Story.